OCPD, the Driven Personality and the Healthy Compulsive — Jungian Analyst Gary Trosclair and Imi Lo

Today we have Jungian Analyst Gary Trosclair, talking about what he calls the Driven Personality, and what we clinically call Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder.

I love how Gary highlights the positive aspect of the driven personality. In his words, a healthily compulsive person can use their natural disposition in service of love, compassion, and the greater good. Even if we struggle with tendencies of being overly driven and perfectionistic, we can transform this trait and use it for the best.

We discussed many things, including the differences between OCD and OCPD, how drivenness fits into the Jungian Hero’s Journey, and what many therapy models may be missing when it comes to overcontrol.

A SHORT TRAILER

ABOUT GARY

TRANSCRIPT

Gary: Good morning, Imi. Very happy to be here talking to you.

Imi: Oh my god, yes. I am very, very delighted to have you. I came across your work and your book a while ago. And I thought you touch on a subject that, as a clinician, I am familiar with. I have close family members who struggle with what you write about. And I absolutely am seeing it increasingly more and more in my clients. So, I thought, “Gosh, I would really love to have you and your input on this.”

Gary: Well, thank you for doing that, because it feels to me like it’s a topic that’s really been neglected and misunderstood, as we might talk about later, confused with OCD. But also, it’s something that’s so accepted in our culture, we don’t understand the downsides of it.

Imi: Oh, I completely agree. I think our society perpetuates the myth of drivenness. Actually, we haven’t told our audience what we are going to talk about.

Imi: Why don’t you tell us what our subject matter is and how you would phrase it?

OCPD — Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder.

Gary: Okay. So, we’re going to be talking today about Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder. I also refer to it as the driven personality at times. Now, this is different from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, which we’ll get to later.

Imi: Absolutely. Yeah.

Gary: But this is a personality disorder, which is one of the most prevalent personality disorders in our culture. Yet, it’s probably the least understood. And part of my goal with The Healthy Compulsive Project, which is the title of my book and the title of my blog, is to take the disorder out of it and help people to understand what the positive potential is that underlies this personality pattern, because it’s not necessarily a bad pattern. Well, I should give some description of what this personality pattern is.

Gary: It’s a personality pattern that’s characterized by control, orderliness, and perfection. And you see it in people because they’ve got lots of rules, they’ve got lots of lists. Things have to be in a schedule, they have to be a certain way. They’re overly conscientious, they’re far too worried about work, often to … They leave our relationships, they leave out leisure. And it’s a very deep-seated pattern. It’s not just like Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, which is just about specific compulsions and obsessions.

Imi: Which is OC-

Gary: This affects the entire person. OCD, yes.

Imi: Yeah, OCD, which is very … You know? Our culture talks about it a lot. And that in itself is actually very misunderstood. I might have another episode about OCD itself. But I do really want our audience to know that what we’re talking about today is not OCD, it’s OCPD, which is something different. And I absolutely love the title of your book, and the fact that you try to de-pathologize something that is so human and it’s so understandable that we have developed this trait of coping or style.

Gary: Yeah, the way I think of it, it’s like these personality traits can either be very positive and healthy, or every unhealthy and negative, maladaptive. It’s just like water and ice. It’s the same material. But in the unhealthy compulsive, it’s frozen, it’s rigid, it can’t move, it can’t flow, it can’t be like the Dao.

Gary: But all of these traits that are at the bottom of OCPD can be very adaptive. In fact, I think that a lot of the great leadership and great work and creativity that gets done in the world is often done by people who are driven and who have compulsive characteristics. So, it’s all potentially positive. But what we need to do is help people to be aware of it so that they can use that very energy to make their compulsive traits to be adaptive and healthy and helpful.

Overcontrol — The Positive Side of the Driven Personality

Imi: Are you aware of a trait called over-control?

Gary: Yes, I have heard of it. And that certainly would be one characteristic of it. And that’s why I have been using the word … The metaphor of being driven.

Imi: Yeah.

Gary: You can be driven in the sense of, I’ve got lots of energy and I want to move forward. But it can also have the sense of being over-controlled and driven by something else, by something I’m not aware of. Carl Jung would use the phrase over-controlled might be a complex, it’s something that’s driving me, rather than me consciously driving and being in the driver’s seat.

Imi: So, actually, to fill our audience in this well, one of the reasons I would love to have you on is I know that your perspective is Jungian, which is an approach that is really close to my heart. When I talk about over-control, there is now some new people doing something called Radically Open Dialectic Behavioral Therapy.

Gary: Right.

Imi: You have heard of it?

Gary: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Imi: Yeah. So, I think in that realm, they’re doing a lot of work around that trait called over-control. But when I look at your work, I think you take a slightly different angle.

Gary: Yeah, I think it’s much larger, the way I conceive of this personality style. It’s not just about controlling, it’s about moving forward.

Imi: Yes, you have that element of drivenness to it. It’s not just about inhibition, which is more what that trait over-control is about. Yeah.

Gary: Yeah. And you know, I’ve read some of that work on Radically Open DBT. I think some of it can be positive. But my concern is that some of the methods and some of the approaches to deal with this missed the central point of going back and understanding what’s at the bottom of these urges that feels so irresistible. These urges are not necessarily bad. I mean, a lot of the great creative work that’s done in the world is done because people have irresistible urges. And thank goodness they didn’t ignore them, you know?

Imi: Absolutely.

Gary: Problem is, if these urges get hijacked by a need to prove ourself, to prove our goodness, to prove our worthiness, our lovableness, that’s when the water gets frozen, that’s when we get desperate, when we get rigid, and we say things have to be a certain way. The difference between a healthy compulsive and an unhealthy compulsive is that the healthy compulsive uses their natural disposition, their talents for achievement and for drive in service of love and compassion and the greater good. And they do it consciously.

Gary: The unhealthy compulsive has that energy and those inclinations, those are hijacked to prove to themselves and to the world that they’re okay. So, the healthy compulsive is motivated by love. The unhealthy compulsive is motivated by dread.

Imi: Two things I want to comment on. One is, gosh, it’s so hard to draw a fine line between the two, because even in myself, I can see both. I can see the healthy drivenness. And obviously there are days where it taps into the unhealthy side.

Gary: Yes.

Imi: So, it’s not one way or the other. And the other thing is, I really love the fact that you used the word hijacked, because it’s like we’re being taken over by something bigger than us. And I think a lot of pathology and creativity, both good and bad, can often feel like that, like there is an inner force or an external force that we just can’t name.

Gary: Yeah. And it’s a shame that it does get hijacked because it can be a very destructive personality pattern. I mean, I get a lot of correspondence from people whose partners have OCPD. And it can break up families. But I think even worse, all the potential benefit that our society would get from people who are driven, where the drive gets hijacked or usurped into less productive things.

Imi: Actually, I wonder if we should actually go back to the drawing board, because we have excitedly dived in. But maybe we need to tell our audience what OCPD is and maybe both according to the DSM and what it looks like in real life, and your definition of it?

OCPD Subtypes

Gary: Okay, sure. So, OCPD is a personality disorder. That is, it’s a pervasive pattern of character and behavior and feelings that’s present throughout one’s life, usually starting in late adolescence and early 20s. It affects the entire personality. So, that’s-

Imi: The definition of PD has to be.

Gary: Yeah. And there are 10 different personality disorders. This is the most frequently occurring.

Imi: Oh, is it? I thought it’s … I heard the other day, because obviously the one that’s most talked about is obviously borderline.

Gary: Yes.

Imi: But you’re right, a lot of cluster C PD has been neglected for some reason, both clinically and in the wider world.

Gary: Yeah.

Imi: But I thought avoidant is the one that’s the most prevalent. Maybe we need to check.

Gary: That’s not what I’ve heard. I’ve heard it, if not the, it’s tied maybe with avoidance. But it’s certainly near the top.

Imi: I’ll check as we speak. But go on, let’s tell our audience what the DSM criteria.

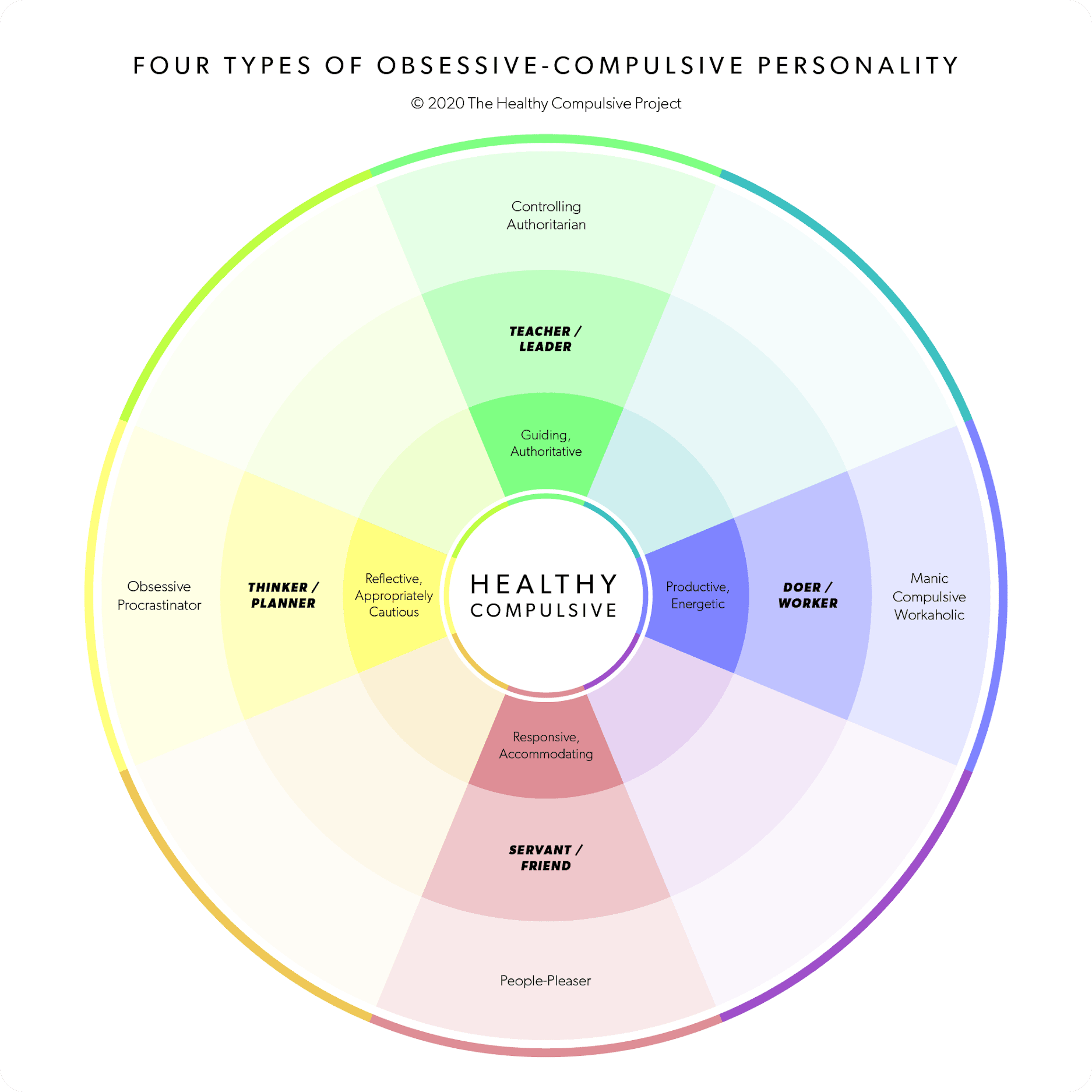

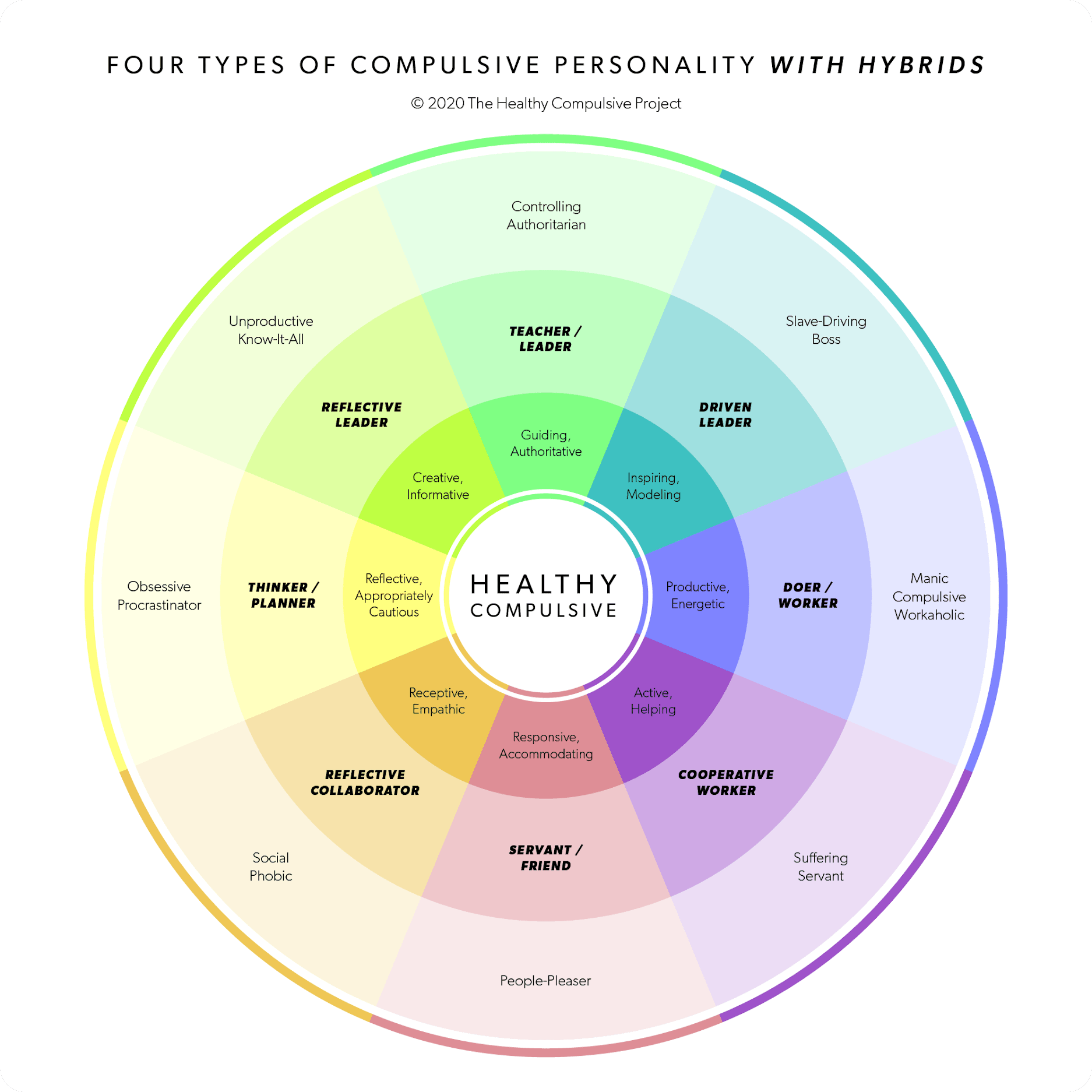

Gary: Okay. And I won’t try to go through all eight of those criteria. But there are eight criteria having to do with being overly conscientious, too much attention to work, difficulty in delegating, being rigid and stubborn, losing the point of the list and the schedules and the rules. There’s another way I might be able to describe this that might be helpful to our audience. There are actually, as I see it, the four different types of compulsive people. And they’re all overlapping, there are no pure ones. But I think this’ll help people to get a flavor what it can look like.

Gary: One is the leader teacher. And this can be very positive in that they suggest ways to do things, way to look at things, and they take leadership. If that turns sour, then you’ve got somebody who’s really bossy, domineering, controlling. You get a partner like this and it can be a really tough marriage, okay? So, that’s one type, and that’s the way it manifests is that they’re so controlling that they forget about other people’s feelings and they forget what they’re trying to teach and what they’re trying to lead for.

Gary: The second type of compulsive, I would describe as the doer worker. These people at their worst become workaholics and they neglect family and friends and they neglect their own body and they neglect leisure. But this can also be very positive. These people can be very productive.

Gary: A third type, I call the servant or friend. And these are people who put their perfection and their energy into not disappointing others and to helping others. And they’re more of a follower. I’m a little reluctant to use that word because it has some connotations I don’t want. But I think you get the feeling of it, that their perfectionism goes into doing what other people might want of them. Again, this can be very great, they’re very cooperative. But it can also mean that they become desperate people pleasers, and they lose track of themselves and what they have to offer the world.

Gary: Fourth type I call the thinker planner. And they can be very reflective and helpful that way. But what they can also do is, they become procrastinators. These are the obsessors as opposed to the doers. And they get stuck in their procrastination because everything has to be so perfect.

Imi: Right.

Gary: These are all different elements of the compulsive personality, they just emphasize a particular aspect of it.

OCPD as the most prevalent Personality disorder

Imi: Wow. That’s very thorough, and thank you. And really, having these characterizations really helps bring it to live. By the way, I’ve just checked. There are two … You were absolutely right and I was wrong. There is one older study in 2004 that says OCPD is definitely the most prevalent PD with 7.88%. But I tried to find a more recent one. There’s one in 2018 that still says OCPD has the highest prevalence at 12.32. I think the first one was just American. The second one is across all Western countries. But yeah, god. It’s in the culture, it’s very much in the culture.

Gary: Well, that’s interesting, I’m curious. Do you see it as much … I mean, you’ve lived all over world.

Imi: Yeah.

Gary: Do you see it as much in other cultures? Have you noticed a difference in American culture as opposed to Asian culture?

Imi: That is such a good question. You know, well, obviously I am drawing generalizations when we talk about cultures and my cultural observations.

Gary: Sure.

Imi: I think certain cultures really have traits that traits of OCPD is almost fundamental to their culture.

So, in the four types that you describe, because you’re a therapist too, which type would you think you see the most?

Gary: I probably see the doer the most and the helper the most. And obviously there are hybrids between those, between all of these. But those are the two that I see the most. The ones that become bossy and authoritarian, it’s much harder to get them into therapy because they’re absolutely convinced that they know the right way, which by the way, is often a characteristic of OCPD or any personality disorder is that they’re okay with their personality. And it’s harder to get them into therapy unless their marriage or their partnership is falling apart.

Imi: Yeah.

Gary: Or they might have gotten feedback at their work that they’ve got to work on something.

Imi: Absolutely. And it’s interesting, I think your conceptualization is similar to mine that there are almost two subtypes. One is afraid … Not afraid, but wary of vulnerability and expressiveness. And the other one is more wary of disapproval.

Gary: Yes. Yeah. I wish I could show our audience right now how I conceive of this because I conceive of it as a Mandala. At the top quadrant is the leader. At the bottom and diametrically opposed is the servant friend. On the left side of it is the thinker planner. And the right side is the doer worker.

Imi: Right.

Gary: If you think of this as a Mandala, what we’re trying to do is to be in the center of the Mandala and integrate all of these in a balanced way. The further out you are out to any of these parts of the Mandala, probably the more severe your OCPD is because you’re just living in one particular way, rather than in a rounded way.

Imi: Yeah. Well, if you have that and you don’t mind, if you can send it to me, I can put it on the website and the show notes and people can access it.

Gary: Okay. I’ll do that.

Imi: Yay.

Gary: Okay.

NATURE/ NURTURE?

Imi: Absolutely. Do you think there are … Nature and nurture. How much do you think it’s nature? How much do you think it’s nurture? What are some of the nature elements that you think may contribute to it? And what are some of the nurture or family or environmental factors that contribute to it?

Gary: Yeah, well of course, there’s a lot of debate about this. But most of the research that I’ve seen leans toward the side of nature. That is, a fair amount of this is based on genetics. There’s a split twins study in Sweden, where they were able to … It’s a longitudinal study where they were able to go back and look at people that had the same genes exactly, but were raised in different environments. And it does seem to be that the genetic aspect is a larger aspect. It’s not to say that the family doesn’t influence it and the environment doesn’t influence it. But some of the characteristics, in fact many of the characteristics of OCPD do have genetic sources, perfectionism, meticulousness, energy, attention to detail, determination, the ability to delay gratification. All of these things do have some genetic basis.

Gary: Now, the environmental part is also important. If you have parents that themselves are OCPD or controlling or they’re intrusive, over-protective, chaotic, insecure in terms of their attachment. And one other one that I want to make sure I add is that you can also have parents that are so praising, you know? And you can do nothing wrong. The child knows that they’re not like that. So, they’re going to feel insecure because they’re not living up to how their parents see them. And it appears that the parents are being very generous. But they feel like they can’t live up to this, so they have to work extra hard to be this person that their parents think they are.

Imi: I keep wanting to interject. But yes, this I see a lot because I work with gifted people as well, people with high intelligence. And if their giftedness was spotted early in their lives, usually they are the golden girl or boy, and they just become … This pressure just mounts higher and higher and higher. And then, on the other side, you also get kids that grew up in disorganized, chaotic families where they had to step up to be a little grown-up from a very young age. They are not allowed to miss anything, to make any mistakes. Yeah, sometimes a question I ask clients very early on is, “What happens in your house when someone spills the milk? What happens?”

Gary: Yeah.

Imi: And you get a flavor, absolutely.

Gary: Sure.

Imi: And you also get very, in a family that really … It’s a stereotype, but you get family that really praises the tiger moms, that praises performance. Yeah.

Gary: No pair of parents is going to get everything right.

Imi: Yeah, absolutely.

Gary: And I think what we need to do is to come to terms with their limitations. I think an important part of this discussion about environment versus nature is that there is … Well, actually three or four elements, but I want to stress a third element here, which has to do with the strategy or the coping styles that we adapted to adapt to our parents and our environment, because some people rebel and some people comply.

Imi: Yes. Absolutely.

Gary: And we develop a whole strategy when we’re young that becomes such a deep part of us that part of being able to transform out of this into a healthy compulsive, we need to understand what the coping strategy that we developed was so that we can use it more in a conscious way.

Imi: Yes. I completely agree. It’s too lenient to say A causes B.

Gary: Yes. Yeah.

Imi: It’s A plus a million factors, plus your natural temperament and the coping styles that you have chosen. And then it creates a personality configuration.

Gary: Yeah. And I’m concerned, sometimes people read psychology. And they say, “Oh, parents have an effect on their children.” True. But we don’t want to leave them feeling that it’s a fait accompli, you know? That they can’t grow or move out of it or even learn from it and have it help with resilience.

Imi: Yeah. And I do believe we don’t come into this world as blank slates. In fact, there were many studies done about sensitive children. Some children are more threat sensitive, they are more wary of strangers. Elaine Aron’s work of highly sensitive … The highly sensitive person talks about this. And there are many other earlier research of infant studies that talk about it. It’s part natural temperament, part nurture. Sometimes there just isn’t a fit.

Gary: Yeah, exactly.

The Driven Personality from a Jungian Perspective— The Hero’s Journey

Imi: Absolutely. So, this is exciting. I mean, you have already addressed this. But how would you understand a driven personality from a Jungian perspective? Is there something unique that the Jungian perspective offer?

Gary: Yeah. Well, part of what I love about Jung is he asked the question, what is the symptom for? What is the neurosis for? Not just what caused it, you know? “Did your mother drop you on your head when you were a kid?” He said, “Where is it leading you? What is it trying to work out?” And so, I think that in the driven personality, there is a very large quotient, share of what we call individuation that people who are driven have a lot of this instinct in us to grow psychologically, to make things, to solve problems, to change things. But that deep tendency can get hijacked.

And it can be displaced onto less important external things. And we often lose the fact that part of what the whole individuation thing is about development of the personality. And I think we have a very large share of this, those of us who are driven. And that if we can become aware of that instinct to develop ourselves, then all those energies can start to come into focus in a much more productive way.

Imi: So, what makes a Jungian way of working with compulsivity different to other ways like CBT or the RODBT that we’ve mentioned earlier?

Gary: Okay. Well, I’m not trained as a CBT person or RODBT but my sense is that one of the most important things about Jungian work is that we see the unconscious as an ally in the process.

Imi: Oh, I love that.

Gary: It’s a source of wisdom and it’s a source of growth and development and inspiration. If we see the unconscious just as a storehouse of repressed memories, there’s an antagonistic relation set up with it. But if we understand it to be the source of great wisdom and energy and direction, then we look towards it to align and to align ourself with it. So, for instance, sessions are going to be much less structured than DBT or-

Imi: I’m guessing people with OCPD do not like that. No structure, no instruction, no rules. You can’t get it right or wrong. Mostly you can’t get it right.

Gary: Yeah. Yeah.

Imi: So, I’m not thinking they like it. But maybe that’s exactly what they need.

Gary: Yeah, well this is one of the reasons why I wrote my first book, which is called I’m Working On It In Therapy: How To Get The Most Out Of Psychotherapy, because-

Imi: I’d love to talk to you about that. Yes.

Gary: Yeah, because psychodynamic work, as Jungian work is, is less structured. And we don’t always know what to do with that lack of structure. And I’m afraid that as therapists, as dynamic therapists, we don’t always explain to our clients how this works. And so, you’re right, it can be a little disorienting for people who are driven, who have compulsive tendencies. And I often have learned that I need to say, “Okay, here’s what we’re working on, and here’s how we’re doing it.” But the difference in Jungian work is that I will try to orient them to the unconscious as a source of wisdom.

Gary: And so, here again, the sessions are less structured. There is probably some emphasis on dreams. I do find that a lot of compulsives don’t remember their dreams because they’re so focused on doing things in the outside world. But it’s that shift from outer work to inner work that we’re trying to achieve through Jungian analysis, which I think is different. It’s less about, I’d say compliance. But it’s more about being able to connect with that source of direction inside.

Imi: very powerful. And how empowering it is, that, because I think a lot of people with compulsivity or a bit of behaviors, they see something in themselves as their angst. Like, I have this monster inside of me that is doing things that I don’t like. But what you’re saying is all parts inside us, no matter what they’re doing, are our allies. We may not understand why it’s looking like that. But ultimately, they are trying to help. And there is a source. There is some internal wisdom that we can ultimately fall back on.

Gary: Yes. Very well-

Imi: And perhaps our job … Yeah, thank you.

Gary: Exactly.

Imi: And perhaps our job is really just a little nudge, a bit of a guidance. But ultimately, they really have this limitless inner source that they can fall back on, which taps into something universal.

Gary: Yeah. Archetypes. So, some of these inner parts of us are individual versions of something that’s much more universal. It could be the judge or it could be the hero, which you might want to talk about in a minute.

Imi: Yes, please.

Gary: But before I get to that, as you were saying, we want to be able to relate to these inner parts in a healthier way. Jung developed a method called active imagination in which we actually have a dialogue with these inner characters. Might be a character we meet in a dream, a character that just comes into our mind through fantasy. We can even dialogue with a mood. But the idea is to develop that relationship, and in the process that character will probably transform and become more adaptive and helpful.

Gary: I mean, think of a dream where you’re being chased by a monster. You turn around and face it, there’s a good chance that monster is going to become much more of a helpful aspect of you. Like, How to Tame Your Dragon, you know? Like that film where the boy helps to heal this dragon, and it becomes his ally.

Imi: That reminds me of that quote from Rainer Maria Rilke, which is, “Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act just once with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.” Isn’t that beautiful? That’s like my favorite quote. I remember having it printed on my name card when I first started out as a therapist.

Gary: Yeah.

Imi: What were we talking about? We were talking about the archetype of the hero, which I really want to hear about.

Gary: Right. Sure. Yeah. Well, since I am a Jungian analyst and I’ve been working on this issue of the compulsive personality for a long time, I often wondered, what archetype underlies the compulsive personality? And eventually, I realized that it’s the archetype of the hero. If you look at the characteristics of the hero, this determination to do the impossible, this determination to be unflappable, to do the right thing, to be conscientious, and all this energy that’s so characteristic of the hero, those are the things that people with OCPD aspire to. Whether they actually live it out in a heroic way is a different question. But that seems to be the archetype at the root of it.

Gary: Now, one can become a heroic compulsive, or one can become compulsively heroic. The difference is, if you’re heroically compulsive, then you’re mindful about how you use your hero energy. If you’re compulsively heroic, you’re just out there jumping into fires and trying to rescue people and doing crazy things and working 30 hours a day. That’s compulsively heroic, that’s not heroically compulsive. So, again, it’s that theme of whether you’re going to be healthy in this role and use your skills and your tendencies in a constructive way, or whether they are going to drive you.

Imi: That’s just good. That’s just beautiful. I feel quite full already with what we’re addressing. You talk about the difference between addressing the symptoms versus healing the personality configuration. And you talk about the many phases clients bring into therapy. Can you talk a bit more about that?

Gary: I’m sorry, you said the phases of work in therapy? Sure.

Imi: I think you had that in another book, how the clients use it. And actually, to be more precise, you said to understand our psyche, we can map it out into three main parts: the child, which is the needs and desires, the parents, which are the shoulds, S-H-O-U-L-D, shoulds. And the adults.

Gary: Yeah.

Imi: Can you expand on that? Because it feels like such a variable and unique model.

Gary: Sure. I was borrowing from transactional analysis.

Imi: Yeah, yeah.

Gary: Which is a type of therapy developed in I think the late 60s, early 70s, in which the understand the personality in these three main parts, the parent, adult, and child. Now, these are very similar to Freud’s superego, ego, and id. The id being the childish energy, the ego being the adult, and the superego being the parent with its shoulds. And I think it’s a relatively simple way of understanding the personality. There are lots of other personality parts. But just starting with this and applying it to the compulsive personality. In the compulsive personality, we like to think that we’re driving our car, but it’s really the parental shoulds, the superego that’s always driving the car. And the child is locked up in the trunk.

Gary: Part of the work is to be able to engage the child. In dreams of compulsive, you’ll often see dreams of neglected children that need attention, that want desperately to play. We need to get them out of the trunk. Say, “What do you need from me? We can’t go have ice cream every day. And we can’t spend all day at the playground. But we can have ice cream once a week and go to the playground five times a week, you know?” That voice that I was just using is what we might refer to as a healthy ego or the adult voice.

Gary: The adult voice realizes that it should not be too severe with the child, that the shoulds are important, but they can’t be running the show the whole time. These are, in a way, versions of archetypes. There are lots of other archetypes that are involved with this, with the compulsive personality, including the judge, the hero, as we said before, the rescuer. Sometimes priests or the prophet, because sometimes-

Imi: It reminds me of the deck of Tarot.

Gary: Yes, exactly. I draw from that sometimes, because those describe a lot of the archetypes that we see and encounter in ourselves and in other people.

Imi: Do you still enjoy doing this work?

Gary: Sure, I do. It’s very challenging, very rewarding. You can never stop learning. And it’s very gratifying to see people change.

Imi: Do you attract mostly clients who struggle with OCPD nowadays?

Gary: It seems to be getting that way more because of my book and my blog. And I think originally it kind of started that way partially because I work in midtown Manhattan. And Manhattan is just a magnet for people who are driven, whether it be attorneys, CEOs, people in finance. But also, artistic directors, you know? People who have a drive to get their creativity out there. Yeah.

OCD vs OCPD

Imi: Wonderful. I think one final thing we might have missed, and I just want to take it back to make sure we cover it before we finish, what do you think of the media’s portrayal of OCD? And many people confuse OCD with OCPD. What do you think are the … I mean, there are legitimate differences. But can you say a bit more so our audience are clear about it?

Gary: Sure. Too often, I think they kind of merge the two. If you think of Jack Nicholson in the film As Good As It Gets, he’s actually a mishmash of the two. On the one hand, he plays this character who is extraordinarily condescending to other people, treats other people very badly and is very isolated. The other hint he’s clearly got OCD, he has to use plastic utensils when he goes to a restaurant, he can’t step on a crack, and all these very specific obsessions and compulsions.

Gary: And they merged the two together. It’s unfortunately misleading, because while OCD and OCPD do often occur together, there are a lot of differences between the two that I’d like to talk about for a moment to get it clear. First of all, OCD is an anxiety disorder. OCPD is a personality disorder. It affects the entire personality in a much deeper, profound way. People with OCD don’t like their symptoms. People with OCPD are proud of their personality at the far end of the unhealthy spectrum of it, okay?

Gary: People with OCD have very specific obsessions and compulsions, whereas people with OCPD, it affects the entire personality. People with OCD don’t necessarily repress their emotions. People with OCPD will repress their emotions and they delay gratification. So, I could go on about these two differences. I can-

Imi: It’s very good. It’s very good. Keep going.

Gary: Yeah. Well, people with OCD will seek treatment for themselves. People who are at the far end of the OCPD spectrum, the unhealthy ones, usually will not seek treatment unless they’re forced to by a partner or a job. OCPD traits can be adaptive, you know? You can get a lot of work done, you can be very good at what you do because of it. Most OCD traits are not adaptive, except perhaps hygiene. People who have OCPD spend their time working on projects and planning. People with OCD spend their time on their rituals, you know? Like, they’re always cleaning. They’re always trying to make things ordered, in order. Now, people with OCPD do that sometimes, but they’re much more focused on larger projects and work.

Gary: So there’s, to me, a very different feel between the two. OCD has, to me, an even more genetic, biological aspect to it, tends to respond better to medication and CBT. Whereas, OCPD, as I understand it, responds better to a dynamic way of working, as opposed to medication or CBT. Now, having said that, I’ve worked with people who had OCD, didn’t necessarily focus on it, but it remitted over time, even though we were doing a deeper form of work.

Imi: Wow. That is very thorough and very clear.

Gary: Well, it’s really a shame because many people are misdiagnosed with OCD for years and treated with medication or CBT, when what they really needed was a more dynamic form.

Imi: Absolutely.

Gary: Now, I don’t want to make too many generalizations, because I think when we practice, whether we say we’re an OCD … I’m sorry, a CBT therapist or a dynamic therapist, we both borrow from the other side, you know? And I think there’s a lot of overlap between the two. But I am concerned when people are misdiagnosed and they don’t get the proper treatment for that diagnosis.

Imi: And my understanding also is, these guys, they need something relational. They need a corrective experience that is felt in their body, rather than learning a set of skills, a set of practices to do, which they will try to do it perfect.

Gary: Yes. Yeah, which brings me to a point that I do want to emphasize on all of this, that people take this healthy water of the compulsive or driven personality, and it gets frozen when they don’t feel secure, when they don’t feel like they are enough somehow, and they have to prove themselves. And I think that a dynamic work is more likely to reach that, which is not to say that CBT therapists don’t develop relationships with their clients. I have a feeling that many of them do. But I think often the deeper work with the unconscious that has to do with unconscious conflicts, which is the way psychodynamic work began, it addresses those unconscious conflicts that are going on inside of these people all the time, but between the child and the parent, you know? Between, on the one hand wanting to do everything perfectly, but then the other part of them that’s left out like, “I just want to have fun,” you know? But it’s in the trunk, so we don’t get to meet it.

Imi: Yeah. Yeah.

Gary: It’s a shame, I think, for many people who have compulsive personality, especially bad OCPD. They have a really hard time relaxing and enjoying life. They go on vacation and they’ve got to make it the most perfect vacation. And if things don’t go exactly to plan, it ruins the whole vacation for them, which is really sad, because they need it.

Resilience and Ending Note

Imi: I know. Well, on that note, let’s end on something more positive.

Gary: Okay.

Imi: What is your definition of resilience, Gary?

Gary: The way I see resilience, it’s the capacity to use adversity in the service of one’s personal growth. You might have heard of the Philosopher’s Stone. This is in alchemy, it’s the substance that can turn lead into gold. And the capacity for resilience to use the difficult situations in our lives as opportunity for growth is what can … It can change our lives by always looking at things through that lens. The last chapter of my book on therapy, I’m Working on Therapy, is all about going into the fire of developing resilience. It’s possible to spend too much time in the fire, but if we have that perspective of, how can I use this in terms of my psychological growth? That changes things a lot.

Imi: Thank you. Finally, can you show us a book or a quote that has changed your life?

Gary: I think the book that changed my life the most was The Inner Game of Tennis by Timothy Gallwey. I read this when I was-

Imi: I’ve not heard of it.

Gary: I was probably 18. Timothy Gallwey was a great tennis player. And he was in the junior national championships. And he was about to win. It was match point, and he missed an easy shot. And so, he went on a quest to find out what happened and why he missed it. And he got into zen. And he realized that he wasn’t trusting himself as to how he played. And this is the thing that, I think helped me to understand psyche in general, to be able to trust something inside of me that will guide me.

Gary: So, when I go to hit a shot, and I love to play tennis. If I’m worried about how my elbow is bent and the angle of my racquet, I’m going to miss the shot. If I trust myself and I think, “Where does the ball need to go?” I’m much more likely to hit the ball where it needs to go. So, it’s all about trusting something inside, which is very much aligned with Jung’s whole approach to psyche. So, it’s the Inner Game of Tennis.

Imi: And it’s so hard, and that trust has been beaten out of us by so many factors for many of us.

Gary: Yes. Yeah.

Imi: It would be so much more powerful, we will be so much more powerful and resilient in the world if we can reclaim that trust in our inner animal.

Gary: Yes. Yeah.

Imi: Well, thank you so much for all your input. I have really appreciated it. I love your energy. I love your wisdom. And I like your angle on things. I feel like we can chat more and more about this. And thank you so much for agreeing to come.

Gary: Well, thank you very much for having me. I have enjoyed our discussion. Okay.

**

Trigger Warning: This episode may cover sensitive topics including but not limited to suicide, abuse, violence, severe mental illnesses, relationship challenges, sex, drugs, alcohol addiction, psychedelics, and the use of plant medicines. You are advised to refrain from watching or listening to the YouTube Channel or Podcast if you are likely to be offended or adversely impacted by any of these topics.

Disclaimer: The content provided is for informational purposes only. Please do not consider any of the content clinical or professional advice. None of the content can substitute professional consultation, psychotherapy, diagnosis, or any mental health intervention. Opinions and views expressed by the host and the guests are personal views and they reserve the right to change their opinions. We also cannot guarantee that everything mentioned is factual and completely accurate. Any action you take based on the information in this episode is taken strictly at your own risk. For a full disclaimer, please refer to: https://eggshelltherapy.com/disclaimers/

Imi Lo is a mental health consultant, philosophical consultant, and writer who guides individuals and groups toward a more meaningful and authentic life. Her internationally acclaimed books are translated into more than six languages languages and sought out by readers worldwide for their compassionate and astute guidance.

Imi's background includes two Master's degrees—one in Mental Health and one in Buddhist Studies—alongside training in philosophical consulting, Jungian theories, global cultures, and mindfulness-based modalities. You can contact Imi for a one-to-one consulting session that is catered to your specific needs.