Table of Contents

Second-generation immigrant struggles are multifold but largely overlooked by mainstream media and academia. It is common knowledge that immigrants worldwide have faced several challenges when trying to build a new life in a foreign land. However, second generation immigrants face an additional layer of complications as they must try to reconcile the cultural identity of their parents’ home country with their own.

All over the internet, we can read how much we admire immigrants’ work ethic and values. But for second-generation immigrants, i.e., children of immigrant parents, their challenges, such as intellectual and cultural chasms, language barriers, feelings of marginalization, and identity confusion, are rarely addressed.

In this essay, we will discuss the struggles and traumas of second generation immigrants; We will also address more tabooed topics, such as how to let go of the unconscious guilt of eclipsing one’s parents, codependency, parentification trauma, and how to end the cycle of intergenerational trauma and become truly free.

“She filled my head with dreams, telling me I could become anything I wanted. I believed her so much I thought I could be white.”

― Still Life With Rice

Definition: Who are Second Generation Immigrants?

Let us first define the term ‘second generation immigrant.’

If you search the internet for definitions, you will find conflicting information. The confusion is understandable because the term ‘second generation immigrant’ itself seems like an oxymoron. Some refer to children born as ‘first generation’ in the host country as ‘first generation immigrants’ rather than ‘second generation immigrants.’

This article will use the United States Census Bureau definition (the Canadian government has also adopted a similar definition). According to them, first generation immigrants are the first foreign-born family members to become citizens or permanent residents of the United States. These are usually the ‘immigrant parents.’ Second generation immigrants, on the other hand, were born and raised in the United States and had at least one foreign-born parent.

In other words: If you have immigrant parents who migrated and you were born here, you are considered a ‘second generation immigrant.’

8 Second-Generation Immigrant Struggles

Second generation immigrants carry unconscious guilt

Immigrant parents are often lauded for their strength and perseverance in the face of adversity, but what is not discussed as much is how much unconscious guilt their children carry.

Poll a group of immigrant parents, and you’ll get a sampling of what each dreamed for their children’s futures. Safety from violence if they’ve fled war or political unrest. A good education. Better housing. A future without limits. If you are a second-generation immigrant, your parents likely emphasized the importance of furthering your education to secure a well-paying job because they want you to have what they didn’t.

You may have witnessed your immigrant parents working two jobs simultaneously or in jobs where they were disrespected and tested. They didn’t have enough money to buy nice clothes or get leisure time for themselves. They tried hard to conceal their daily struggles, but you could see it on their faces, and you knew their bodies ached. You might have thought you were too young to feel responsible for your parents’ sacrifices, but even if your guilt escaped your conscious mind, it is impossible to erase the memory of witnessing their hardship.

Some immigrant parents resort to emotional blackmail, reminding their children of everything they’ve sacrificed. The implication is clear: “You better choose the life I would have chosen if given the options you have.” Most other immigrant parents do their best and never mean to guilt-trip you, but you still feel the implicit pressure to please and repay them.

Second-generation immigrants often feel unjustifiably responsible for events over which they have no control. All children inherently blame themselves for bad things that happened to their families. But with the background knowledge that your immigrant parents emigrated to ‘give you a better life,’ your guilt is more pronounced. When you saw them struggling, your young mind assumed that you had done something wrong or that you should have done more to help them. So you studied harder, did more housework, counseled them, became their emotional clutch, and even punch bag. You tried everything to be an even better child than the obedient and diligent child that you already were, but your parents’ struggles persisted. This resulted in compounded guilt (‘I did not do enough’) or even shame (‘ I am not enough/defective’). The latent belief was that you could not put your immigrant parents out of their misery and that they may have suffered because of you. Such unconscious guilt or shame can have a significant impact on your life even now. As an adult, you may sabotage your relationships, health, and career because you feel you don’t deserve a good life. When you do achieve things, you do not feel able to celebrate them for fear of making your parents feel bad.

Unconscious guilt can also manifest in various seemingly unrelated ways: You have a dysfunctional relationship with money and feel unable to properly care for yourself. You become a prisoner of your own inner drill sergeant, overworking constantly and feeling guilty for relaxing or having fun. Regardless of your external accomplishments, you feel like an imposter. At work, you allow yourself to be abused or exploited. You may have bottled up all your struggles and sadness as a child because you were taught that you don’t have the right to complain. Even in intimate relationships and friendships, you are wary of burdening others to the point of showing no vulnerability. (See: Overfunctioning in Relationships)

To heal from this major but typical second generation immigrant struggle, you can embark on an inner reflective journey to uncover the origins of your unconscious guilt and shame. While your feelings feel real, they are logically unfounded. You had not done anything bad or wrong; you did not decide your parents’ paths for them, and you could do little as a child to save them. You had not taken anything away from them. If anything, you have been an absolute blessing to your parents. It is evident from existing research and literature that immigrant parents’ primary motivation is to promote their children’s well-being and prosperity. Whilst a small part of them may envy the economic advantages and opportunities you have, deep down, the healthiest part in them genuinely wants you to thrive.

Even though you have no control over the source of your guilt or shame, you can work to undo them and live the life you truly deserve.

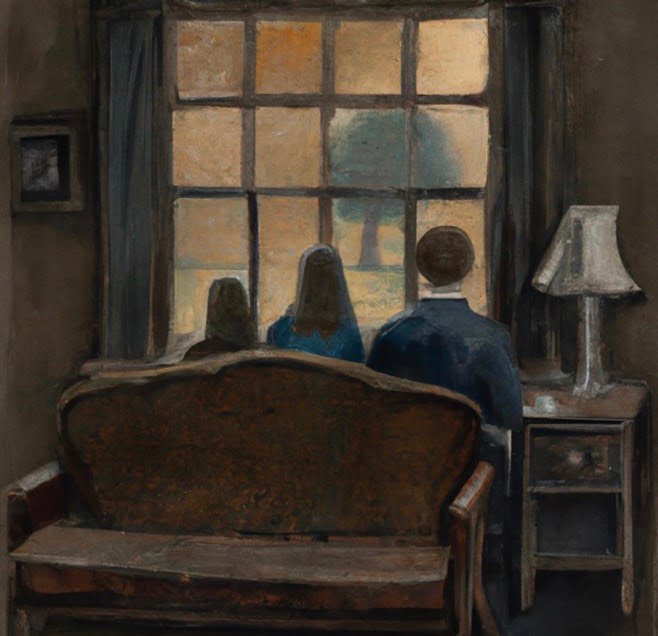

Second generation immigrants feel rootless

Identity crisis is the second most salient, but not surprising, second-generation immigrant struggle. If you were born to immigrant parents, you would have spent your entire life “between” the culture of your parents and the culture of the country where you live. In the academic literature, cultural identity is viewed as a kind of “positioning” rather than a fixed aspect of the self. The identity of second-generation immigrants is plural, fluid, and constantly changing. Your identity is neither rooted in the history of the old country, as with your parents, nor in a purely Eurocentric adaptation to the new country. Instead, you are always in a ‘transition zone’ that feels untranslatable in its complexity (See Stuart Hall, Cultural Identity and Diaspora). Identity and acculturation must be understood in the context of broader sociological factors such as colonialism, war, and immigration policy. Issues of lost privilege and racial oppression must also be considered. In the complex web of trying to reconcile everything while finding your way, growing up straddling two cultures has likely taken a heavy psychological toll on you.

As a young person, it might have been almost impossible for you to find a middle ground between your parents’ beliefs and those of your peers and community. You could not put your struggle into words, but you were torn every day between holding on to the roots of your ancestors and fully appreciating the culture in which you live. The guilt of getting what your parents sacrificed may have led you to believe that it is wrong to have both cultural identities and that you are forced to choose.

You may have been conditioned to behave one way toward your family and another toward your friends. Perhaps you have felt ashamed for enjoying a component of the new culture sanctioned by the old. Something that is celebrated where you live may be condemned in your parents’ hometown. For example, American society values personal freedom and autonomy, which may be at odds with your immigrant parents’ more collectivist, family-oriented values. If you are constantly hiding one or more aspects of your personality to fit in like a chameleon, you may not have had the time and space to explore and solidify your identity. The result is that you no longer know who you are. The lack of inner cohesion can also lead to a chronic sense of emptiness and a background feeling of depression that you can not shake. Even now, you may have difficulty making important life decisions, such as choosing a career path or entering into meaningful relationships.

You long for the day you can find your tribe. Still, repeatedly and traumatically, you can only find “otherness.” Growing up, you were ‘too foreign’ in your home country — you spoke with an accent or spoke none of your parents’ mother tongue, you were too ‘Westernized,” etc. But you were also too foreign to feel entirely at home where you are — the color of your skin, the economic hardship of your parents, the lack of Westernized family rituals— all of these screamed “otherness.”

You end up feeling rootless and like you do not belong anywhere. For you, the boundaries between ‘here’ and ‘there,” “self’ and ‘other,” are constantly shifting like the weather. The unfortunate reality is that even when a racist tells you to “go back to your country,” you have no country to go back to. Your parents may have it, but you do not. This is the only country you have ever known or experienced.

Outgrowing your roots: the intellectual gap with immigrant parents

The next second generation immigrant struggle we want to address here is slightly tabooed. That is the intellectual gap between you and your immigrant parents and the fact that they could hardly keep up with you. You are not alone. Many second-generation immigrants experience a gulf of disconnection between themselves and their parents due to disparity in education, cognitive abilities, and cultural experiences.

As a second generation immigrant, especially if you are relatively intelligent and intellectually curious, as you grow older, you soon painfully realize how vast the chasm is between the parents you ideally wanted and the parents you have. You may find that other families can have stimulating conversations about current events while your parents seem stuck in the past and in their old, limited world. At home, there were no intellectual or political discussions about big ideas, and your parents have shown no awareness of issues like diversity, feminism, the dark side of capitalism, etc. Pressured to survive, all they seem to care is the mundane and practicalities.

If you are educated, informed, well-traveled, and open-minded, the intellectual gap between you and your parents can make even the most basic everyday interactions unbearably difficult, if not painful. This is especially true for emotionally and intellectually intense truth seekers who can not help but see their parents’ potential and the gap between things and how they could be.

If you are gifted, you generally find ignorance, narrow-mindedness, and false judgments intolerable. As a result, when your parents say or do things that go against your values, you can’t help but feel uneasy or compelled to challenge them. Correcting them, however, only brings defensiveness and ends in passive avoidance or conflicts. You can’t help but judge your parents, but you feel incredibly guilty about it. You don’t know who to complain to about how existentially lonely you are in your own home, so you keep your resentment and frustration to yourself. After all, you respect and love your parents, but it can be difficult to be fully yourself when spending time with them.

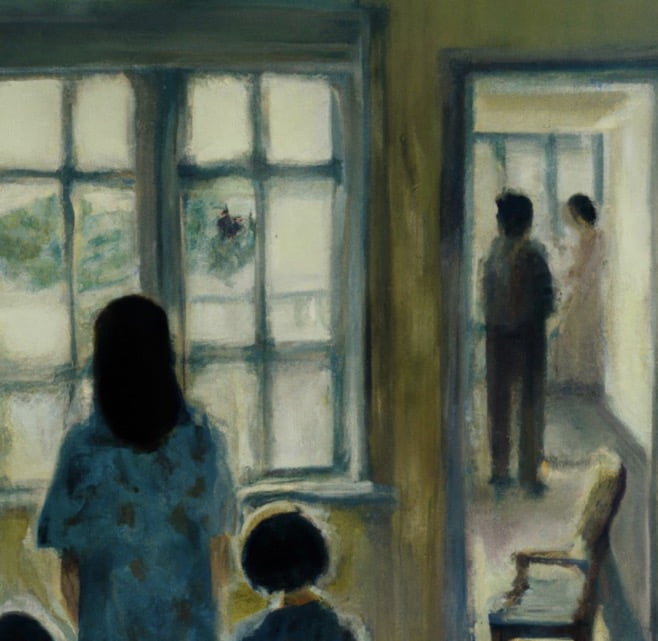

Your immigrant parents don’t see or get who you are

It can feel like all that matters is that you meet your immigrant parents’ standards and expectations. They expected you to get good grades, to be home at certain times, and to complete your assigned chores and duties. But there was no genuine interest in discovering who you truly are beneath the ‘good child’ facade. This isn’t because they don’t love you, but the strain of starting over in a new country has left them with no time to be curious or appreciate the deeper essence of who you are.

Furthermore, your immigrant parents may not have had the broad horizons or ability to fully comprehend your place in the world. For example, they may believe you are successful because of your high GPA and a steady job. But they just don’t the point. They are oblivious to your brilliance and why it is so. Your immigrant parents, for example, do not recognize your unique and gifted ability to think for yourself, reject “group think,” courageously defend the truth, and have a deep commitment to social justice. They may also fail to recognize what distinguishes you from others: your perceptiveness, empathy, and intuitive understanding of other psychology and human dynamics.

One of life’s most harrowing trials is trying to be ourselves around people who don’t seem to see, hear, or understand us. The wound of being labeled as ‘too much’ (too emotional, too dramatic, too demanding, too intense, too sensitive…) is especially deep if it occurs within our own family. Even if we try to rationalize it by saying we are materially provided for, the pain of not being acknowledged and seen for who we are can cause immense grief that lasts a lifetime.

Your grief stems from your inner child’s desire to be seen by their parents – the only parents they ever had. Rather than trying to mold you into something you’re not, you justifiably hope that they will appreciate the unique qualities you bring to the family. When you gain knowledge, you want your family to grow alongside you. You want them to help you thrive, not just survive, and not with criticism but with encouragement.

If they only ever project their ideals onto you, it can push you to resort to developing what psychologists call a ‘false self’. When a child’s genuine expressions and spontaneity are rejected, he or she is forced to create and maintain a fictitious persona to avoid abandonment. If you hold onto your false self to an extreme degree and for an extended period, even as an adult, you may be left with only a ‘persona’ and an empty core. When you hide your innermost thoughts and feelings from others and yourself, you may feel empty, dead on the inside, inauthentic, and as if you are living someone else’s life rather than your own.

It is not uncommon for people who have lived with a ‘false self’ for too long to have a quarter-life, midlife, or existential crisis, in which the regret suddenly haunts them that they have stifled their full potential to protect their parents.

If this happens to you, please remain hopeful and know that your identity crisis can also be a portal of growth and breakthrough, allowing you to finally reclaim your life as a vessel for your immigrant parents’ unlived lives. We will discuss more in the next section.

“It is a curious thing to realize, the in-betweenness one feels being African American in Africa. It gave me a hard-to-explain feeling of sadness, a sense of being unrooted in both lands.”

― Becoming

Your immigrant parents judge you

Your immigrant parents may judge you unfairly for your life choices or simply for being yourself because they have a limited worldview and do not know the world as it is now. Unfortunately, when your parents do not understand the significance of your chosen paths and endeavors, they cannot support them.

They may judge you for who you are with, your chosen career, whether you are single or married, whether you prefer polyamory or monogamy, and so on. To make matters worse, many of the things they consider “choices” are your innate traits. These include your personality, sensitivity, intensity, intolerance of conventional standards and mundanities, your ADHD trait, being trans or gay, etc. They have no choice but to reject you because any deviation from what they know scares them. Even if they try to hide their bias, they may undermine you with seemingly insignificant remarks, facial expressions, or punitive silences.

Their judgment is based on ignorance and an outdated understanding of the world. For many baby boomers, the world continues to be a linear space where one must climb a traditional career ladder and a standard life trajectory to be happy and prosperous. Perhaps they were taught in churches and schools that being gay, autistic, or neurodivergent in some way means you are ‘less worthy” in life. Authenticity, diversity, and inclusion were not known or understood in their formative years. (Of course, not everyone in their generation is the same; this is a gross, perhaps unfair, generalization!)

They most likely did not intend to hurt you, and whatever hurtful things come to your way result from their unconscious bias. However, if you are highly sensitive and empathic, you will undoubtedly detect signs of their criticisms even if they don’t say anything. It’s nearly impossible to ‘unsee’ what you see, and despite what they grudgingly say, they’re not wholeheartedly supportive.

Some parents are willing to learn new things and try to understand the new world. Other parents, on the other hand, remain defensive and abusive.

If you have repeatedly tried and failed, you may choose to not directly confront them. But that does not mean you should suppress and deny your feelings. Even if you choose not to “pick fights” with them, you must allow yourself to process the emotional pain you have suffered.

A part of you may be tempted to rationalize the feeling of unfairness. You can justify the situation by saying, “They did their best,” or “It’s not their fault.” But even if these statements are true, it makes no difference to your emotional reality. It is sometimes necessary to allow yourself to process and release your feelings.

Being upset or angry at your parents for something does not mean you do not love them. Love and rage or resentment are not mutually exclusive feelings. You can be frustrated with your parents while still admiring what they do for you or how much they love you. You can admire their good intentions while still being offended. To have an authentic relationship, you must be able to dance in a dynamic that includes both conflict and love.

Only by acknowledging and processing your true feelings will you avoid becoming stuck in a loop of guilt and resentment, which is the last thing your parents want to see. They may have hurt your feelings and did not intend to, but they cannot make it right. As an adult, it is now up to you to heal and move forward.

Second generation immigrants are often emotionally deprived

Many second generation immigrants find that, while their material needs are met at home, their emotional needs are largely neglected. Factors including economic hardship, cultural norms, transgenerational trauma, the need to combat racism, and feelings of inferiority may all have contributed to the emotional poverty at home (Chung, 2016).

Immigrant parents have struggled internally with grief for their hometown, the absence of familiarity and support, the trauma of racism and discrimination, fear of deportation, and feeling like an imposter no matter how much they achieve. However, when they had to make ends meet and were under immense pressure to ‘make things work,” they had no space to process their feelings. What if their grief and sadness overwhelmed them so much that they could no longer turn up to work? What if they opened the emotional floodgate and could not close it, so they collapsed into depression? These fears meant they had no choice but to suppress any bubbling sadness and put on a stoic facade. Immigrant parents simply could not afford to break down.

The fact that they hid their vulnerabilities for so long inevitably caused them to lose touch with themselves and become wary, if not afraid, of emotional signals. So when they see you showing vulnerable feelings like shame or sadness, they do not know what to do. Whether consciously or unconsciously, they must prevent you from expressing your emotions to keep their fears under wraps. They may do this by ignoring, punishing, silencing, or telling you in various ways that it is wrong to express feelings.

Anger is one of the most commonly suppressed emotions in an immigrant family. Because of the pressure to assimilate into a new culture, your parents may be reluctant to express their anger for fear of being shunned and alienated. As a result, you have internalized the message that anger is inappropriate or shameful. Unfortunately, chronically denying yourself of the right to be angry can lead to other mental health struggles, such as paranoia and depression. It also leads to a sense of disconnection and exacerbates loneliness. If you never learn to recognize, process, or even feel anger, you will have difficulty standing up for yourself and forming meaningful relationships with others as an adult. (See: Repressed Anger and the Highly Sensitive Person)

Another reason for emotional suppression might be cultural norms and values. Men in Latino cultures, for example, are expected to follow traditional gender roles and demonstrate strength and manliness at all times. Showing vulnerability is seen as a sign of weakness rather than humanity.

In many Asian countries, especially those with more ‘introverted’ cultures, such as Vietnam and Japan, explicit, outward expression of feelings is seen as a sign of immaturity and lack of discipline. Instead, children are encouraged to be quiet and cooperative so as not to be a burden to others.

Furthermore, in many Asian households, showing negative feelings such as anger and disappointment toward adults such as parents or teachers is a sign of disrespect. Second generation Asian immigrants in a Western country may struggle because of the gap between their “internalizing” home culture and their “externalizing” school culture. They are taught to suppress their feelings at home, but they are encouraged to speak their minds at school. The gap between their social circles at home and school has left them feeling befuddled and confused about their identity.

Some Asian children feel emotionally deprived as their parents never explicitly expressed love and affection. While they see their Western peers receiving hugs and kisses from their parents, they have never heard an ‘I love you’ from their parents. As Rebecca Zhong, a Chinese Kiwi second generation immigrant, recalled: Growing up, I was envious of my classmates’ parents. They seemed nurturing and kind, whereas mine were stoic and stubborn. We never expressed affection towards one another, we never uttered “I love you,” and we never conveyed gratitude (Debate Mag, 2020).” Of course, this does not mean that Asian parents do not love their children. It’s just a difference in love language, but the dissonance can be difficult for a child’s mind to navigate.

Given how wary of emotions and vulnerabilities many immigrant parents are, it is not surprising that many of them also have little mental health awareness. This means that even if you have legitimate mental health difficulties, your parents may inadvertently prevent you from getting the treatment. They might not be taken seriously if you had legitimate mental health needs. Your immigrant parents might interpret your depression as laziness, your eating disorder as rebellion, your ADHD as a character flaw, your Borderline Personality Disorder as attention-seeking, and so on. The idea of seeking help from a therapist or psychiatrist may be utterly foreign to your immigrant parents, let alone knowing it costs money. Needless to say, delaying necessary psychiatric treatment can have serious consequences that last a lifetime.

Many immigrants live in a small community (in an ethnic neighborhood or church, e.g., Korean American Churches), which makes them wary of the possible stigma if someone learns that they or their children are seeking mental health help.

Even if you did not realize it at the time, the effects of growing up in a home where emotions and mental health needs were denied, repressed, and banished become abundantly clear when you meet other families or try to form close relationships with others. For example, you may not be able to express your feelings or form meaningful relationships with others because you have internalized the belief that it is unacceptable to show emotion, have emotional needs, or be vulnerable. (See ‘Do you Allow Yourself to Take up Space?‘)

“Her fear that I would not mature paired with her hope that I would someday have power. Because she didn’t have any power and being an immigrant mother was a half-life.” ― Joan Is Okay

The immigrant parent traps: parentification and codependency

In immigrant families, it is common for parents and children to develop an unhealthy level of co-dependency. Co-dependency has many faces, but at its core, it is an unbalanced relationship in which one partner’s sense of self-esteem and self-worth depends on how much they can give up for the other. Co-dependency includes behaviors such as rescuing and overhelping.

In immigrant families, parentification, a term that describes children being expected to take on the role of an adult and provide for their parents (a form of role reversal), often occurs along with codependency. Parentification can occur in a variety of ways. Some examples include requiring the child to take on household chores such as cooking or cleaning at an early age, babysitting younger siblings while parents are away, counseling an emotionally vulnerable parent, standing in as a surrogate partner (also known as emotional incest) or even having adult-parent conversations about financial issues or serious matters that a child should not be involved in. (If you suspect you have been subject to Parentification trauma, here is a thorough article on this subject).

When children assume parental responsibilities too early, they become overwhelmed, confused, and traumatized. They begin to believe that they are only loved for their utility (what they do) rather than who they are inherently. They grow up unable to trust their self-worth nor believe they deserve to be loved unconditionally. As who they are is not seen or heard, many are left to struggle with life-long identity confusion and inner emptiness. They do not. Usually, the oldest child is most likely to become parentified, although this may not always be the case, depending on the siblings’ personalities. If you were parentified, you were essentially deprived of a carefree childhood. This leaves a gaping hole that can never be filled. Even as an adult, you may struggle with excessive guilt, be overly responsible for others but also resentful of others in relationships, have difficulty making decisions or setting boundaries, and so on. In some cases, this can even lead to physical health problems because you are overly stressed and hypervigilant for most of your life.

When co-dependency exists between children and their parents, a toxic bond characterized by anxiety and insecurity is created. You may constantly feel like you have to take care of your parents’ needs first, blame yourself for their problems, worry about them constantly, feel responsible for their happiness, be unable to say “no” or set boundaries, and neglect your own needs because you are too focused on them.

In the long run, when you are stuck in a co-dependent dynamic, it causes you to feel highly conflicted and ambivalent towards your parents, and you find yourself in a dilemma of love and anger. Part of you is obsessed with the mission to save your parents, while the other part is filled with anger and resentment because you know you were stunted by parents who were so helpless or dysfunctional that they could not be real parents to you. This is a complex issue, but as the awareness of it grows, there are many books and resources that can help. There are even support groups for co-dependency (called CoDA) that you can access.

Fortunately, it is possible to heal from a dysfunctional relationship if you are aware of it and seek appropriate help. This does not necessarily mean completely breaking up with your parents, but it is about finding a more mature and sustainable way to love them.

The unseen weight of internalized oppression as a child of immigrants

Another second-generation immigrant struggle or identity crisis comes from the pain of having internalized shame and society’s oppression. Being a part of an immigrant family, you may have witnessed and been subjected to institutional discrimination, microaggressions, and racism as a child. Unfortunately, you were exposed to the dark side of our society too soon and were powerless to stop it. London-based writer Renee Kapuku, whose parents are Congolese and Nigerian, writes about her experience poignantly: “Watching how the person at the post office talks down to your father because he has a slight accent. Seeing how your parents are spoken patronizingly to at parent’s evening. Watching them alongside you, get to grips with the harsh reality that is a place that was never meant, and will never be, for any of you.”

Even as a child, you felt that something was wrong, that you should be ashamed of something, but it didn’t make sense. Even if if you were unable to put a name to them, the lingering feelings of worthlessness, powerlessness, shame, or humiliation may lead to many negative self-beliefs such as “I am not good enough” or “I’m not worthy” that you take with you into adulthood.

Or, perhaps, you noticed that when you spoke in a native accent, people treated you differently. The disparity in treatment between you and your immigrant parents, on the other hand, may leave you feeling blameworthy.

Repeatedly witnessing injustice and oppression without being able to do anything will result in what psychologists call ‘learned helplessness.’ You might have developed an unconscious belief or mindset that says no matter what you do, your efforts will be futile. This can have a long-term impact on your self-esteem and sense of agency.

At the same time, you may feel increasingly overwhelmed by the world’s injustices and corruption. You can’t ignore or tolerate them, but you’re also stuck in believing that the task of making changes in the world is so vast that you’re powerless to effect anything meaningful.

“With just about every script, in almost every corner of the set, I was faced with the truth: This was my parents’ life. My mother had sat in handcuffs; my father had once worn an orange jumpsuit like the dozens that sat folded in our wardrobe department. “

―

Overcoming the Legacy of Pain: A Second-Generation Immigrant’s Journey

Grieving the family you desired but never found

One of the most striking unspoken second generation immigrant struggles is the wish that one’s immigrant parents could be different. You may wish for parents who are intellectually on par with you, who are not racist or narrow-minded, and who are not on the other end of the political spectrum. You want parents with whom you can have real, exciting, and stimulating dialogs, who understand you, and with whom you can have a fair and authentic discussion about issues in life and the world. It is taboo to complain about your intellectual gap because ‘everyone’ thinks you are who you are because of their sacrifices, so it is thought that it would be a sin to be perceived in any way as ungrateful.

No, it’s not that you are not grateful for everything you have been given. It’s not that you do not appreciate their sacrifice. You are incredibly grateful, but that does not make it any easier to be a child who has to physically, emotionally, and intellectually take care of their parents. The most painful struggles of having immigrant parents are the nameless ones– what should be there but is not–sensible guidance, humor, playfulness, and the fact that even after all these years, they do not seem to see you for who you are.

Aside from safety and security, children have basic needs such as being seen and heard, feeling connected, having autonomy in making decisions, and having their feelings acknowledged and mirrored. If these needs are not met, you are traumatized, even if your trauma is hidden behind material wealth and academic achievement. Being emotionally deprived as a child can leave a lifelong longing for something more and something different.

To move forward, we have to grieve for the parents we fervently wished for but never got. It is perfectly okay to acknowledge your longing and disappointment. You may have spent your whole life denying your resentment toward your parents. Only when you are healthier and more resilient, and your psyche is finally solid and stable enough to know that it will not collapse in overwhelming grief, can you admit to yourself how disappointed you have been in your parents. In other words, you become psychologically healthier when you can finally break out of denial and feel anger, however unpleasant it may be.

You may not want to confront them directly. Still, it’s perfectly okay to at least admit to yourself that parentification has hurt you, that you have been dragged into codependency, that you have been forced to play a small role in life to protect them from their fears, and so on. All feelings are valid and do not have to be “justified” or “fair.” If you are sad and resentful, you have the right to be. Just because you want more from your parents does not mean you do not love them.

Even in their absence, you can talk to a therapist or someone you trust, write a journal, or do something to help you process your feelings. Allowing your grief to happen does not mean you will wallow forever in regret over missed opportunities. Grieving is about taking the time and space to process your feelings and accept reality for what it is. You will feel more liberated as you engage in this process. It may seem counterintuitive, but the truth is that if you can allow yourself to process your anger and resentment toward your parents, your rage will no longer erupt in unexpected places (such as throwing a tantrum even when there is no apparent trigger). Once you’ve grieved the “perfect parents” you deserve but never had and reconciled with the fact that these two humans allocated as your parents would never be able to give you the support, guidance, and intellectual stimulations you so deeply want and deserve, you can make a conscious decision to move forward. At this juncture, you can choose whether to keep fighting for what will never be or choose a different way to love them. The result is that, paradoxically, you will be more patient and loving with them and better able to accept them as they are.

Of course, the caveat is that no mistreatment is acceptable, and there is no excuse for cruelty. Ending a toxic or abusive relationship with narcissistic parents is always an option. But if you choose to stay and have a relationship with them, albeit one that is more healthy and less codependent, you would do well to extend your deepest empathy towards their limitations.

Finding freedom in not trying to change them

You and your parents may disagree on numerous issues, including religion, politics, whether or not to have children, how to raise them if you do, how close you should live, and how frequently you should call or visit. Either you are constantly trying to change their minds, or they are trying to change yours.

What makes things hard is that, despite knowing intellectually that we cannot change our parents, many of us seem unable to shake off the compulsion to keep trying. This is known as ‘repetition compulsion’ in psychology. (Full article on Repetition Compulsion: How to Sop Turning to Parents who Hurt you)

However, by insisting on “helping them,” “teaching them,” and “guiding them,” we are not truly accepting them as they are. By imposing our definitions of “functioning,” “healthy,” and “good” on them, we are not genuinely empathizing. Whilst it may come from love, it is not an act of love but control.

You mean well; you want them to develop positive habits like eating well, socializing, participating in meaningful pursuits, and having enjoyable hobbies. You want them to get along, stop fighting over petty things, become more informed, take care of their health, and stop self-destructive addictions. In other words, you don’t think the way they are is acceptable.

To us, they may be backward, racist, unintelligent, and politically misinformed. Why do they continue to engage in the same dysfunctional patterns or habits? Why don’t they learn new things or read the news? Why don’t they think critically? Why do they hoard stuff? Why do they have such an unhealthy relationship with money? Why do they vote for the wrong candidate? Our judgment can be limitless.

The problem is that no matter how covertly we try to push our agenda, it only triggers more resistance and defensiveness from them. Even when we don’t say anything, if we do not learn to see their choices and who they are from their perspective, we are judging and not empathizing.

You may have to remind yourself that when it comes to our aging immigrant parents, it’s not always a lack of sincerity or a lack of trying; more often than not, it’s a lack of capacity or ability.

We live in an increasingly complex world steeped in postmodern values that say there are no ultimate truths and that everything is socially constructed. But immigrant parents spent most of their lives in a time when there were definite truths and absolute answers. If they lack the capacity for highly intellectual thoughts or abstract reasoning, trying to explain or discuss our values around complex ideas such as queer theories, gender as a spectrum, religious divisions, equality, inclusion, and environmental sustainability can only alienate them.

As for their lifestyle and habits, it is possible that they do not have the inner resources necessary to change. They may fear that they do not have it in them to do otherwise or be ashamed of being exposed by you. Rather than assuming their inability to comprehend is due to laziness, we should look behind their stubborn defenses or avoidance to identify underlying vulnerabilities and limitations.

If you decide it is too uncomfortable; or that the gap between you is too significant for you to communicate, you can choose to distance yourself from them and spend less time with them. We have the right to keep our distance, but we do not have the right to change another person to fit our expectations. This is unfair and an impossible endeavor that only causes suffering on both sides.

A better way to bring about change may be to become a good example and show, not tell. However, people only change if they want to, which is not up to us.

When you realize how futile and destructive your desire to change them is, you may learn to accept them and turn a blind eye to certain things. If the disagreement is not about something of utmost importance to you, you can probably learn to live with your differences and still love and appreciate each other. Acceptance does not mean that you like or agree. You may even tell your parents that you hate or resent certain things they say or do, but once you have communicated this authentically, you can move on. You may even enjoy each other’s company more. This takes effort, but learning to live with disagreement is a higher form of love than trying to change them for what you think is ‘better.’

“I don’t care what baggage they dragged over the ocean. They have no right to make me carry it the rest of my life.”

― Loveboat, Taipei

Breaking the cycle of intergenerational trauma

You inherit your parents’ trauma, but you will never fully understand it’”

Most of the literature on intergenerational trauma initially focused on Holocaust survivors and their families (Danieli, 1998). Since then, many studies have consistently found that trauma can be consciously or unconsciously transmitted across generations.

The root of intergenerational trauma may predate your parents’ experience of displacement and identity crisis when they moved and include the trauma they experienced in their own families. Either through vicarious emotional experiences or attachment deficits, their traumas – fear, paranoia, grief over being uprooted, feelings of rootlessness, shame, and feelings of inferiority – may be passed on to you. For example, if you witness your parents’ fear and hyper-vigilance, you learn early on that the world is dangerous and that you must always be on guard. This can lead to a lifetime of fear and difficulty trusting others. The most toxic and damaging is when your parents carry unconscious trauma and behave in dysfunctional ways (See ‘Parents with BPD’). For example, they may project toxic parts of themselves onto you, punish you for doing things they consider ‘risky’ or ‘too much,” forbid you to be carefree and spontaneous, overemphasize external accomplishments, or be overly protective or controlling … … the list is endless.

Intergenerational trauma can have profound effects that last a lifetime. But since we cannot forever blame our parents, it is now up to you to take matters into your own hands and embark on a healing journey. It is possible to break this generational cycle and recover from the trauma of your ancestors. Many people before you have done it and changed the path of their families.

The first step is to become aware of the dysfunctional patterns you may have inherited from your family. How do you relate to authority and institutions? What is your relationship to money? Do you dare to do better than your parents? How well can you express your feelings and form meaningful relationships with others?

One of the problems with intergenerational trauma is that it can cause us to unconsciously perpetuate dysfunctional family patterns. As a parent, you want to be careful. To start, make a conscious decision about the kind of parent you want to be, and that decision will serve as a motivator as you work toward that goal. In family therapy or at your own home, you can talk openly with your children about your second generation immigrant struggles and share your family’s migration history. Then, intentionally work with your children to find a new narrative they can healthily internalize as third-generation immigrants, which includes an integration of, rather than a toxic denial of, their ancestral past.

If you were subjected to intergenerational trauma in the form of ongoing abuse from your parents – emotional blackmail, financial abuse, name-calling, gaslighting, disregard for boundaries, and so on – it may be necessary to draw boundaries with your parents as an adult. When you do this, your parents or other family members still caught up in toxic co-dependency may try to guilt-trip you or frame you as the ‘black sheep.’ But even just for the sake of protecting your children, you may need to put your feet down and cut contact if they treat you with little respect.

Honoring your existential angst

No matter how far you have come, you may feel obligated to give back to your parents for all their sacrifices so that you and your siblings could have a better life. Your unconscious guilt could even be the main reason for many of your successes in life so far.

Despite all that you have now, however, at some point, you may find that you are missing something else– perhaps you longed for something more soulful, a deeper connection with others and the world, or you were seized by a desire to leave a legacy of some sort; or you miss the sense of lightness, playfulness, and creativity you once had.

Your spiritual/existential/midlife crisis could be triggered by a significant life event, such as losing your job, a divorce, an accident, etc. But it could also just be a growing sense of unease that will not go away, no matter what you try.

At this point, you realize that what got you ‘here” can not get you ‘there.’ According to Carl Jung, most of us spend the first half of our lives trying to make sense of the world. We build a persona (a bit like the ‘false self’ we talked about earlier, but ‘false self’ refers to something more specific in terms of our dynamics with our parents) or a social mask based on external influences such as family, upbringing, culture, and religion. Living in our false self leads us to resist our true destiny and inner calling for much of our lives until we can actively begin to reclaim it in later years.

Consider this long quote by Carl Jung, describing his early life: “Somewhere deep in the background I always knew that I was two persons. One was the son of my parents, who went to school and was less intelligent, attentive, hard-working, decent, and clean than many other boys. The other was grown up—old, in fact—skeptical, mistrustful, remote from the world of men, but close to nature, the earth, the sun, the moon, the weather, all living creatures, and above all close to the night, to dreams, and to whatever “God” worked directly in him…” Jung understanding of himself is that his self is plural— not as in a medically split personality, but a way of describing intricately what happened inside of all of us. Your true self is not a foreign object, however. It has always been there, only hidden and suppressed. Even from a young age, when he had to put on a persona to please his parents and society, Jung was aware of his true self when he was alone. He described: ”At such times I knew I was worth of myself, that I was my true self. As soon as I was alone, I could pass over to this state’.

As a second generation immigrant, you have always lived in a world other than your own, searching for identity while standing alone. You are missing what is inside of you to greet because you are enslaved to your parents’ expectations, which you can’t help but meet. But there comes a time when you must question the status quo of your parents’ history and take on the challenge of discovering your true soul and inner mystery.

Usually, around midlife (though in the modern era, it is often much earlier), we must go beyond our old conceptions of ourselves and reclaim what has been lost. It’s much easier said than done. If you have been co-dependent with them all your life, you may feel guilt or fear when it comes time to embrace your autonomy. You may be concerned that your parents will crumble if you go your own way. You may feel like a ‘bad person’ for abandoning your parents’ value systems and disappointing them. Although you know, these feelings have no logical basis; you cannot help but be governed by them emotionally.

When you feel called by existential angst, you have no choice but to honor it. Resisting the call to your true self will leave you sick, either mentally in the form of depression and anxiety or physical illnesses and pain. Individuation is the most natural rhythm of life, and there is no reason to feel guilty as you are not doing anything sinful or harmful. Individuating as an adult may be temporarily turbulent, but you and your parents will soon settle into a new, more healthy, sustainable equilibrium.

With time and enough practice, you find the strength to let go of the past and write a new narrative that is, at long last authentic to you.

(See Existential Crisis and the Intense Person)

Embracing not just your shadow but also your light

For many second generation immigrants, it is not only their ‘shadows’ (the rejected dark parts of themselves) that need to be re-integrated and embraced, but also their ‘light’ (the rejected good parts of themselves). You might have felt like an impostor all your life. Maybe you have a dysfunctional relationship with your gifts; and think ‘power’ and ‘ambition’ are dirty words. Perhaps you have felt uncomfortable acknowledging your kindness and creativity, and whenever you shine, you fear you are “too much,” overbearing, and a threat to your parents. After all, no one expected the immigrant child to outshine the others – the trauma of internalized shame and racial prejudice has held you back greatly. You have hidden your true ambition because you fear outgrowing, outshining, or threatening your parents. If you were to deviate from a ‘safe path” such as a stable job or a recognized profession (lawyer, doctor, study STEM, marry at an appropriate age, etc.), you cannot imagine how your family would react. To protect them, you played it safe and held back your most creative, playful, and imaginative self.

Reclaiming your light means stepping into your true power and living authentically. Start by no longer shying away from compliments. Instead, learn to consider them as at least partly accurate and enjoy receiving others’ love and appreciation. See if you can stop letting opportunities pass you by but take matters into your own hands and make your desired future happen. You are not arrogant when you step into your light. Instead, it is a generous act. By becoming authentic, you can share your gifts with the world and make the most meaningful contribution you can to the world. After all, that is what your parents want to see and what they have worked so hard to achieve.

“i want to give my dad

a lifetime of peace

for the lifetime he spent

on the road to feed us

i want him to know

what comfort feels like

i want him to see

he’s done enough

– a lifetime on the road”

―

Final Reflection: Whose Fears Might You be Carrying?

Without realizing it, many of us carry around fears, obligations, and burdens passed down through generations.

Usually, these family messages and secrets remain unspoken; only we feel them deeply in our hearts and mind.

For example, someone who has lifelong money fears and insecurity may one day see that the ghost of their grandparents’ poverty still haunts them.

Under the radar of our conscious thoughts, we carry the limited worldviews of our parents, the fears of our grandparents, the pain of our ancestors, and the collective trauma of our race.

We live our lives dragging the burden of guilt over pleasure, the chains that keep us from freedom, and self-sabotaging impulses that keep us from playing big.

The real you, however, is the opposite of such a fear-based existence.

The wild soul within you is infinitely resilient – it can be bent but not broken and bows to the current of life like a champion.

A crucial part of becoming our own person, of adulting, is what psychologists call ‘individuation.’ In individuation, we peel away the fears, pains, and limitations of those who came before us.

This will never be easy, but it makes our existence meaningful and life-giving.

When we work through our intergenerational trauma, we stop the toxicity and unconscious anxieties from being passed on to the next generation. In the truest sense of the word, we “give” life to those who come after us— a more transcended life, one free of transgenerational fears.

When we choose to break away from our family or cultural heritage, perhaps by disobeying our parents’ prescribed plan, separating from family members who guilt and manipulate us, or going against society’s dogma, we are often led to believe, explicitly or implicitly, that we are doing something unjust, disrespectful, or even immoral. But these feelings are groundless and benefit no one. Deep down, our parents do want us to forge our paths and become fully functioning humans.

Getting rid of the burden of ‘the guilt of doing better than our parents is one of the most challenging tasks on our path, but it is essential to free ourselves from the past and grow into our true selves.

If you are plagued by anxiety and paranoia, start by reflecting on this: Whose fears are you carrying?

How much of that is your own fear, and how much of that is inherited?

Times of uncertainty and great anxiety are invitations from life to do some necessary soul cleaning – a stripping away of our attachments to beliefs we thought we needed but which are insubstantial in the first place. It is a time to reconnect with our most authentic, bravest selves.

Think back; rewind.

The little boy or girl in you is content with simple pleasures, ecstatic when you have a brand new adventure, and has infinite imagination when you find a blank canvas.

If you no longer have to be the poster boy/ girl for your family and can afford to fail however many times you want, what worries would you be able to get rid of?

If you never had to hold yourself to their acceptable standards, what non-essential tasks or burdens could you let go of?

If you were responsible for no one and nothing except your own integrity and survival,

How much lighter would you feel then?

To reconnect with your wild soul, imagine a world where there were

No societal pressure or norms

No one ever says you are ‘too much.’

No parents’ disappointment

No sibling jealousy

No doctrines from churches and institutions

No ‘shoulds’

No judgments.

Maybe then you will realize

Your true self can survive with just freedom and will.

Your true self is fiercer, braver, purer, infinitely more adaptable, and at home with nature than you ever dreamed possible.

Written by Imi Lo

For an Audio Version:

Imi Lo is a mental health consultant, philosophical consultant, and writer who guides individuals and groups toward a more meaningful and authentic life. Her internationally acclaimed books are translated into more than six languages languages and sought out by readers worldwide for their compassionate and astute guidance.

Imi's background includes two Master's degrees—one in Mental Health and one in Buddhist Studies—alongside training in philosophical consulting, Jungian theories, global cultures, and mindfulness-based modalities. You can contact Imi for a one-to-one consulting session that is catered to your specific needs.