In recent years, with the proliferation of self-help, motivational speaking and the social pressure to adopt ‘positive thinking,’ the word ‘victim’ has become a sensitive one.

If we were to admit, or even to suggest that we were victimised, we may face judgement from society, or have well-meaning friends stopping us from our ‘victim mindset.’

The idea of ‘victimising’ oneself now gets demonised as being something unhealthy, weak and even immoral. Sometimes, just mentioning negative events, traumatic events, difficult times with our family are forbidden.

“I am not the victim”, “I am not going to be a victim” have become our modern world mantras.

It is as though using the word victim means we are accepting a lifelong sentence of passivity or defeat.

It is as though acknowledging that our parents have hurt us means we are somehow ungrateful, narcissistic, or immature.

But none of the above is the absolute truth.

When the rejection of victimhood is pushed to an extreme, combined with black/white thinking that is so common in our modern media, we become stripped of the right to simply tell the truth as it is.

What is wrong with admitting that at some point in our lives, under certain circumstances, we were victims?

The pitfall in refusing to acknowledge the truth is that we become unfair towards ourselves. We may resort to driving all blame onto ourselves, distorting our memories just to comply with what is allowed in our speech.

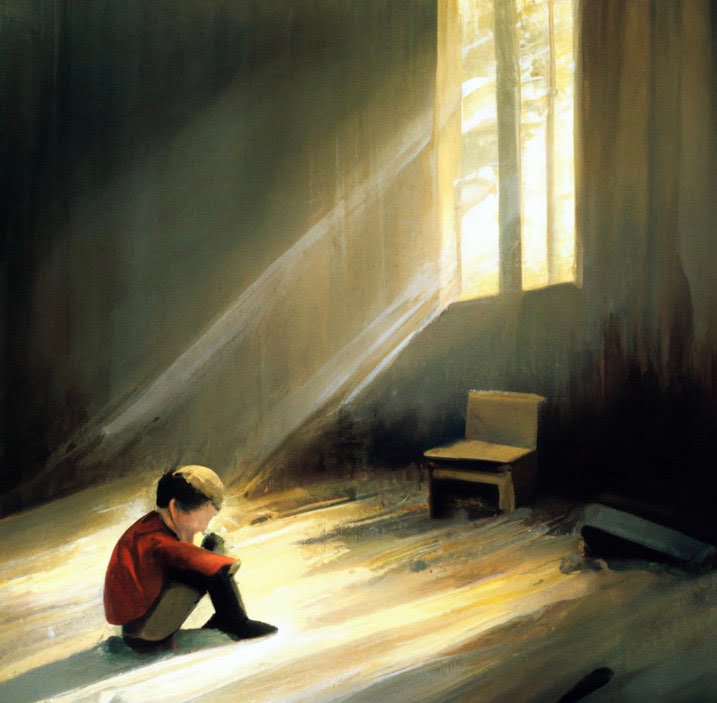

People who were abused, mistreated or neglected in some way as a child often has internalised guilt and shame. They may carry excessive responsibilities in all relationships and tend to internalise their anger. They may become chronically angry at themselves rather than rightfully directing their anger at external events.

Instead of risk getting angry at those they once depended on, they would rather deny their experience, swallow their pain, erase their history and suppress any human emotions they might have.

They may resort to rationalisation or premature forgiveness.

They say things like ‘Feeling upset won’t change anything,’ my parents did the best they can.’ ‘I had a decent childhood compared to many.’ ‘They will never change, so what’s the point of revisiting the past?’ They say these, but without the necessary emotional process and release.

This kind of spiritual bypassing or premature forgiving does not truly free oneself of pain and suffering. The stifled rage had to go somewhere, and often it morphs into physical ailment or misdirected anger.

Suppressing the word ‘victim’ entirely may mean we end up with a tendency to blame ourselves for everything, even things that are outside of our control.

It may mean we look back at our past and act as though we could have controlled anything, or altered any outcome. These are typical illusions of the gifted child.

The healthier approach is to simply acknowledge that in certain circumstances, we were nothing but victims of our predicament, of fate, of a situation that we have no control over.

For example, when we were innocent infants, not out of our human will we were brought to a family that was abusive, neglectful, violent. We could not run away, we were the victim. There was nothing we have done that was wrong to have caused that.

This might be controversial, but I think we must acknowledge that sometimes, we are the victim of a situation.

OF COURSE, WE ARE NOT STUCK

Of course, it does not mean we get stuck in being a victim. Empowering people to transcend victimhood is probably the original intent of the whole self-help movement. Unfortunately, with some twists and turns, this sentiment somehow got contorted into toxic masculinity, and morph into a kind of blame-the-victim activity.

How can we heal, if we are not even allowed to be honest about what had happened?

Acknowledging that we were the victim of our parents’ limitations does not mean we ignore all the good they have done, or the gratitude is there.

It is not a black-or-white, either-or thing.

We were the victim in some cases, but we might also be the recipient of much love, and we can hold both truths.

Acceptance is the gift we receive when we go through this courageous process of seeing and admitting how we were ‘once a victim.’

Acceptance may appear to be a passive act, but it is actually a highly proactive action that propels us towards truly resolving the problem.

Because it’s not what happened but resistance to what happened that is the problem.

Once we have accepted our once-victimhood, we can stop resisting the truth, and we stop resisting the emotions that come from the truth. This way, we free up the energy that we had used to suppress our emotions. This gives us the power to take responsibility for our future.

We cannot alter the past, but we can be wholeheartedly accountable for our thinking, our mindset, and where we go from here.

For example, we can see that because we were once deprived of certain needs, we now project our paranoia and rage onto people who are in our lives today— friends, therapists, authority figures, loved ones. We can then redirect this mis-diverted rage to where it rightfully belongs and improve our relationships and lives moving forward.

We were victims of what happened and the circumstances but we will not be the victim of our own thinking and lack of insight. Through the painful but worthwhile rite of passage of glaring at our past truthfully, we can become fully accountable for our mindset and our reactions tomorrow. Isn’t this the true essence of self-help?

We were once powerless, passive, helpless. but we now have the ability to make the best of what had happened, and summon resources we do have today to get out of the situation.

Admitting that we were once a victim certainly does not mean we are stuck there.

Admitting that we were a victim simply means we shed light on the truth, and free ourselves of blame. As we do that, we are also giving other people permission to tell their stories and free themselves.

Ultimately,

It is not our wounds that make us who we are.

It is what we have chosen to do with our wounds and how we move forward from it that makes us who we are.

We could have chosen a life of denial, suppression and misdirected anger.

We could have spent the rest of our lives lashing out unreasonably at those who love us without knowing why.

We could have insisted that we were ‘never a victim’ and plough forward in life with false stoicism and spiritual bypass.

But we can also choose to not do the above.

We can choose to courageously see the painful truth, however glaring.

We can walk through the ring of fire that is involved in true forgiveness.

We can also hold both anger and love in our hearts, and transcend to a more well-rounded, mature form of love towards our parents.

Perhaps, true love is saying ‘nothing bad happened and you were absolutely perfect.’

True love is saying ‘You have faults and I was hurt by them. But I choose to forgive, though I will not forget what happened,’ and ‘I still love you, but I cannot trust you fully.’

Or, if that is not possible, we say “I choose to honour myself and walk away.’

So. If I may, I would like to suggest that we all stop banning ourselves and others from using the word ‘victim’. It is okay to say we were once a victim. It is even okay to wallow in the sadness and feel sorry for ourselves for a period of time, so we can process the guilt and hurt before we let them go.

This does not mean we are stuck in victimhood.

Admitting once-victimhood is not a lifelong sentence. In fact, it is the doorway to true freedom. It is the most mature way to transcend our past, without pre-maturely bypassing our wounds.

Like phoenixes that rise from the fire, we can indeed be very proud of who we are.

Heroically, we can all be ‘once a victim’, but ‘victim no longer.’

Imi Lo is a mental health consultant, philosophical consultant, and writer who guides individuals and groups toward a more meaningful and authentic life. Her internationally acclaimed books are translated into more than six languages languages and sought out by readers worldwide for their compassionate and astute guidance.

Imi's background includes two Master's degrees—one in Mental Health and one in Buddhist Studies—alongside training in philosophical consulting, Jungian theories, global cultures, and mindfulness-based modalities. You can contact Imi for a one-to-one consulting session that is catered to your specific needs.