Hi 🙂

You might have noticed that the recent few letters on the topic of relationships, including the previous ‘Our Fear of Abandonment and Rejection’, and ‘Our Quest for Love’.

Although not of us are all engaged in intimate relationships or subscribe to the traditional model of a monogamous partnership, there is perhaps value, for all of us, to reflect on our relationship with the world and what we want from others. Some of the themes worth contemplating are: How to be independent and healthily dependent at the same time, how to be emotionally self- contained and not overly-reliant on others, and how to stay present in what we have without excessive worry about losing what we cherish.

I hope some of the ideas addressed in these letters will be relevant and helpful to you.

***

Our Fear of love

– “I do not need anyone, and I can trust no one.”

As the concept proliferates mainstream media and self-help literature, many of us are aware of ‘co-dependency’, and how it holds us back from having fulfilling relationships. What is less known of and spoken about, is the idea of ‘counter-dependency’.

Counter-dependency is the other face of dependency, both stemming from deep-rooted attachment wounds within us. If maladaptive dependency is not trusting we could survive without another, counter-dependency is not being able to trust other people- to take care of us, to be depended upon for big and small practical tasks, or to lean on for comfort or consolation. In terms of attachment theories, counter-dependency is closely related to the avoidant style of attachment (Batholomew & Horowitz, 1991); it develops as a compensation for not being able to count on important others when we were little.

Authors Janae and Barry Weinhold described counter-dependency as a“flight from intimacy”, characterising features such as difficulty being close to others, inability to seek help, perfectionism, having extreme discomfort in appearing or being vulnerable, having problems relaxing and being addicted to activities like work or exercise. Though their conceptualisation is helpful, the descriptions run the risk of pathologising this survival pattern. Perhaps we can see counter-dependency, not as a diagnosis, but as a behavioural pattern that developed out of our childhood adaptation. It was there because it once was a useful strategy, but becomes an issue if we hold it too rigidly, or let it becomes our only way of coping in life.

There are many reasons why sensitive and gifted people are prone to developing counter-dependency. It could be a result of their natural competence and a high need for autonomy, but it could also come from the roles they tend to take on in the family system (the capable one, the surrogate parent, the taskmaster), having inadequate or inconsistent parents. If our parents were not able to attend to us when we had most needed them, we might have internalised the feeling that our existence—including our emotions and our needs —was a burden. So we decide to give up on wanting anything from anyone. In other words, to survive the lack of or inconsistent parenting input, we learned to withdraw our needs from others and even ourselves.

Counter-dependency shows up in our day-to-day life in various ways, and we may not be aware of why we repeat certain behaviours. In counter-dependence we tend to use ‘deactivation’ as a way of coping with attachment triggers, this means we by default shift our attention away from things that arouse strong feelings of intimacy and vulnerability. Here are some examples of conscious or subconscious ‘deactivation’ strategies:

We fear the thing we want the most.

-Robert Anthony

MINIMISING AND FORGETTING

Minimising is when we diminish the hurt that we experience in past or current relationships. We feel unable to talk about our feelings, feel guilty when we get upset with others, or feel ashamed for ‘complaining’. We may feel uncomfortable taking up talking space in conversations and resort to always only being the listener. When we do speak of painful past or current experience, we may narrate them in detached, intellectualised, distanced, and rationalised ways. We say things like: ‘I am sure they don’t mean it’, ‘They do the best they could so there is no point in me thinking about it’.

The father of attachment theories, John Bowlby, believed that this ‘defensive exclusion of information’ has an evolutionary root. In adverse circumstances, it serves our survival to avoid expressing our feelings. If our experience had taught us that being angry would lead to someone deserting us, or that our sadness was a burden, it makes sense that we default to hiding our feelings. We learn to shut off our emotions – first to others, then to ourselves, to prevent potential rejection or exile from the family and community (Sable 2004).

To its extreme, we do not only minimise hurt, but we actually forget about the entire incident or sequence of events. Over a century of psychological research have shown that people who have been through overwhelming experience do develop a kind of amnesia. Using the term ‘betrayal trauma’, researcher Freyd (2001) explained how in order to survive abuse or neglect by a trusted caregiver, some amount of information blockage is required. This is when we find ourselves not able to remember a particular incident or feel we have ‘lost a chunk of time’ in our personal history.

EXTREME SELF-RELIANCE

Counterdependent individuals have a worldview that others cannot be depended on and opt for radical self-reliance. They would rather not seek help or reveal vulnerabilities even in times of needs. In a series of well-designed empirical research of adults in stressful or threatening situations such as military training and being close to death, psychologist Mario Mikulincer found that adults who are avoidant of attachment tended not to engage in support seeking to manage distress, instead of falling back on ‘distancing’ approaches such as distancing themselves from others and significant others (Mikulincer & Florian, 1995, 2000).

Being emotionally self-contained is healthy, but that is different to a defensive denial of our need for belongingness. In mature independence, we do not deny our inevitable interconnectedness with the rest of humanity.

As our need for love has been frustrated, we construct a facade of pretending not to have any needs, and eventually, we start to believe we really don’t need love. Then, we feel our lives to be flat and numb. To make up for our inner emptiness, we try to establish our values through ‘doing’ rather than ‘being’. We might be high-achievers in the professional arenas or appear successful, independent, and self-contained, but deep down our battle with perfectionism, shame and loneliness keep us away from living life fully. Our loneliness is perpetuated as we continue to live with a facade, rather than letting others see our raw, unedited self.

CUTTING OFF

When it comes to forming or sustaining intimate relationships, the counter-dependent person could easily feel smothered or engulfed. We may push people away when intimacy reaches a certain point, or we reject others pre-emptively to avoid hurt. Some of us may even avoid relationships altogether, or have one short relationship after another, to avoid closeness.

When in a relationship, beyond more obvious conflict-avoidant strategies such as silent treatment and retreating, we might also employ other strategies to conceal our needs, such as deflecting when in conversation, rationalising our behaviours, or using work and other excuses to avoid intimacy. When challenged, we might deny our loneliness, emotional needs or the fact that we have a hard time trusting.

In day-to-day interactions, we might find ourselves disengaging when the intensity of the conflict or engagement increases. The phrase “cutting off” (Main 1977) was used to describe a particular posture we could observe in nonhuman species- including turning away the eyes, turning the heat down, and redirecting attention. We might find ourselves retreating to the same stance when conflicts arise.

We might find ourselves feelings and act in opposite directions. ‘Cognitive disconnection’ (George and West 2001) is the process by which our responses become disconnected from the relational situation that has caused them, leaving us confused about the reason behind our behaviours. For example, we may have a lot of ambivalence, stay in a relationship with someone toward whom little or no emotion is felt, feel great uncertainty about our commitment, or get stuck between two partners.

Disengaging and cutting off effect not only our relational landscape but also our inner psyche. If we are ‘cut off’, we do not experience ourselves as a part of the world, nor are we in touch with our psyche. As a result, we experience a ‘void’, a chronic sense of aloneness and inner emptiness.

“When you have a grasp on eternity your eyes won’t ever see the battle or the lost people that hurt you. You will see a beautiful story of hope, in every character.

― Shannon L. Alder

FINDING OUR WAY BACK

If our early experience of life has not been positive; if we had been betrayed, let down, deprived, overly sheltered or smothered, it would be difficult for us to believe that things could be any different.

Even when the circumstances had changed, we continue to live like the small wounded animal that we once were in a cage that our mind creates.

So when something is going well, we do not dare to believe it, as we fear the disappointment that follows.

When someone touches our heart, and offer us the love and presence that we have longed for, we do not dare to let it in, for we are already worried about its ending.

We feel that we are not a big enough container for our dreams, and we are so used to the disquiet longings in solitude that the idea of getting what we want terrifies us.

Living this way, we end up pushing away the love that we most long for.

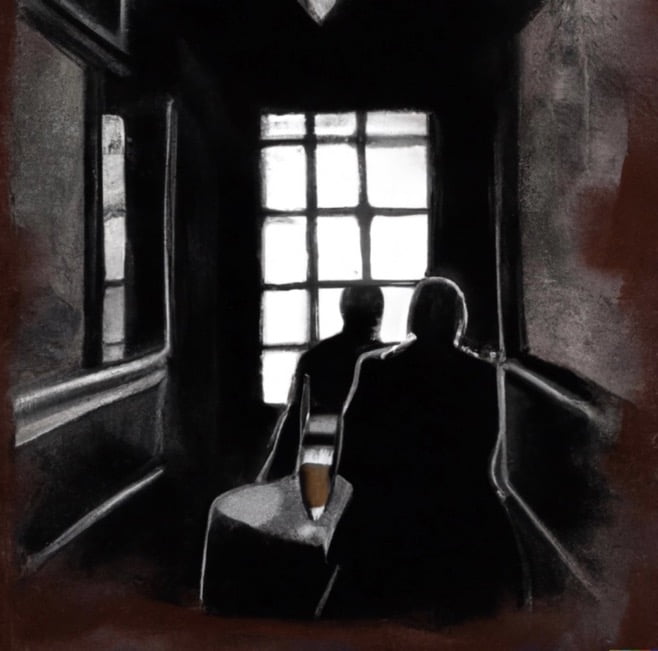

To embrace love is to embrace our vulnerability. Love evokes tenderness— It feels like an unnamable dull ache, yet with butterflies fluttering underneath, a strange feeling that words and images cannot capture.

If we are used to numbing and closing down, love can feel threatening to our system. If we do not slow down and touch in, our automatic response is to push it away. But we ended up in an arid land, empty and disconnected. And every day, our heartaches, and asks: How do I find my way back into love?

“Instead of being fixated on the wrong that had been done to me— the obsession to return to innocence— I began to see my heartbreaks as necessary. Without them, I would never have known true belonging, which is inclusive of exile, not in spite of it.’

– Toko pa

It may seem paradoxical at first glance, but the answer to healing from defensive non-attachment is actually to affirm our ultimate autonomy and resilience.

We push away good things in life because deep down, we worry that we would not survive losses and heartbreaks.

If we know we are strong enough to go through grieve, disappointment and heartbreaks, then placing our trust in someone’s hand would become much less threatening.

To melt away our armour, we ought to feel safe and grounded within ourselves.

We could allow ourselves to graduate from a child-like way of need, into a mature, grounded way of relating.

As an adult, the basis of our courage to trust and to love does not lie in the hands of others but our strengths.

It is not that we have the blind faith that others will not hurt, disappointment or betray us, but we trust that we could grieve, digest the disaster, and bounce back from it. Unlike the helpless child we once were, we are more resourceful, resilient and adaptable than we think we are. We do not have to fear dependency, for we are never truly dependent on another. We are both dependent and independent— and when the time comes, we can summon the strength that is needed to adapt.

As children, we need from others utmost reliability, consistency and availability.

As adults, we rely on our ability to self-contain and self-soothe.

Unlike a child, we know that people can break promises, withhold their love, and change the way they act.

But rather than counting on others to create a haven for us, we do that for ourselves.

We no longer need our partner to guess our needs, fulfil our desires or stand up for us, but we can assert ourselves to the world. We may also become aware of our deprived needs as a child and the longings, and become our own best parents.

We no longer live in fear of ‘being dropped’ as a baby would be; we stand on our own two feet.

Rather than being pulled by insatiable hunger, we simply appreciate the love, attention and respect offered by others when they are freely given.

Then, our understanding of relationships becomes much more nuanced: We do not need absolute safety and certainty, we can hold the paradoxes of trust and disappointment, separation and attachment, and find our ways in the flux of life.

“The ice inside me melts. Suddenly, I’m burning up and terrified, scared I’ll be too weak to resist.

Scratch that – I’m petrified I’ve already given in.”

― Amanda Bouchet

Falling in love and becoming attached to another is one of the most intense, enriching and exuberant experiences of the human life.

So let’s reap the fullness of it.

We shall immerse in the sweetness of intimacy, the joy of finding belongingness in another’s heart, and the ecstasy of discovering ourselves in their eyes.

Yet, when it is time to let go, we also know that nothing ‘bad’ is happening. Even if, temporarily, it means dark nights of the souls or a shattering heartbreak.

Rather than drowning in sorrow, we dance with grief, and we are glad that it had all happened. It is not that we would not get hurt, but it is much better to have lived and loved than not to do so at all.

Even in sadness, we have a quiet knowing that the end of one co-created journey opens the door to another adventure.

Let it all in.

Beauty and glory.

Let life happens for you.

To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable.

— C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves

Click to SUBSCRIBE TO MORE LETTERS LIKE THIS

Imi Lo is a mental health consultant, philosophical consultant, and writer who guides individuals and groups toward a more meaningful and authentic life. Her internationally acclaimed books are translated into more than six languages languages and sought out by readers worldwide for their compassionate and astute guidance.

Imi's background includes two Master's degrees—one in Mental Health and one in Buddhist Studies—alongside training in philosophical consulting, Jungian theories, global cultures, and mindfulness-based modalities. You can contact Imi for a one-to-one consulting session that is catered to your specific needs.

Dearest Imi

You are a shining light …every piece you write blows me away …l feel blessed to ‘met’ you so to speak….thank you SO much xxxxxxx

2 things you wrote really touched me.

"Disengaging and cutting off affect not only our relational landscape but also our inner psyche. If we are ‘cut off’, we do not experience ourselves as a part of the world, nor are we in touch with our psyche. As a result, we experience a ‘void’, a chronic sense of aloneness and inner emptiness." This puts into words something I’ve never been able to explain. What I mean when I say tuning out/cutting off. But in the way I mean it, not to the extent others would.

The rest was the positivity, the groundedness, of being present and real. Although it seems completely impossible.

Thanks for sharing…