Table of Contents

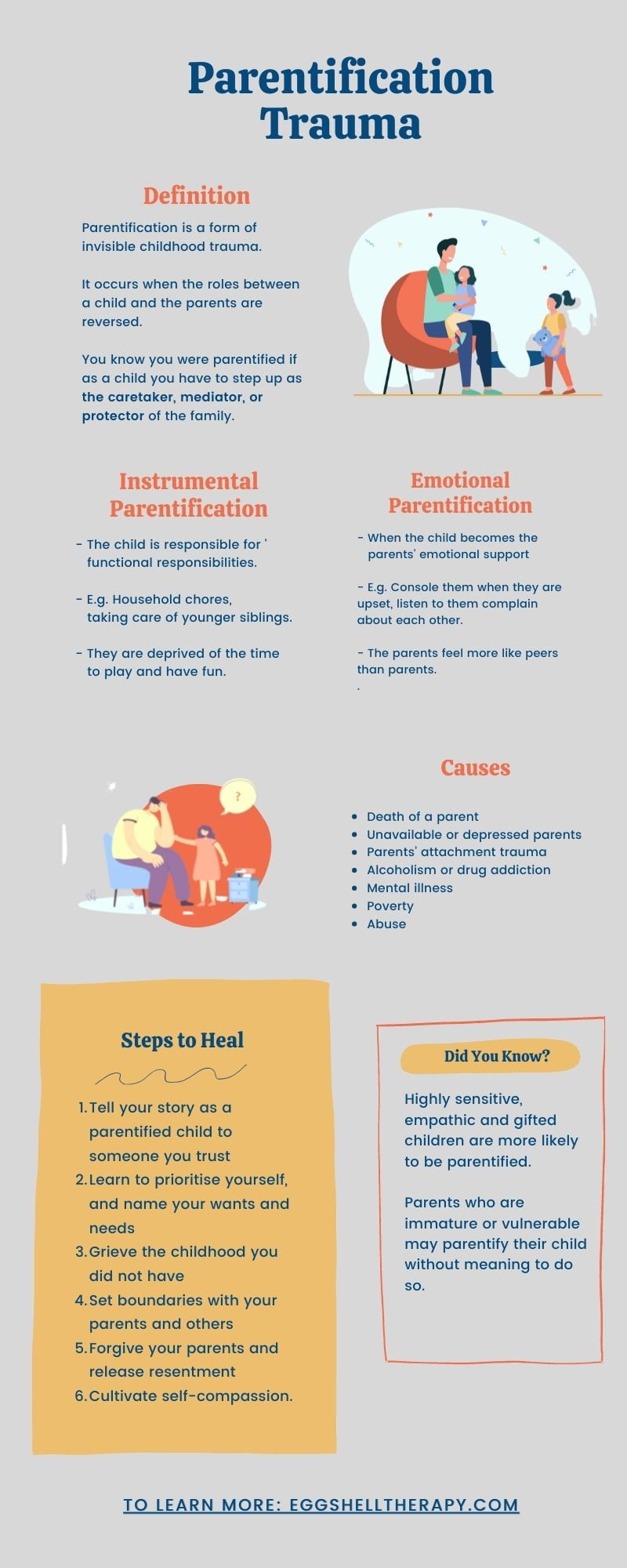

What is Parentification? What does it mean to be parentified? Parentification is a form of invisible childhood trauma. Parentification occurs when the roles between a child and a parent are reversed. You know you were parentified if as a child you have to step up as the caretaker, mediator, or protector of the family. Parentification is a form of mental abuse and boundary violation.

What is Parentification?

Parentification is a toxic family dynamic that is rarely talked about and is even accepted as the norm in some cultures. However, research has found that it can have far-reaching negative psychological impacts.

Parentification is when the roles are reversed between a child and a parent. Researchers have defined parentification as follows:

a disturbance in the generational boundaries, such that evidence indicates a functional and/or emotional role reversal in which the child sacrifices his or her own needs for attention, comfort, and guidance in order to accommodate and care for the logistical and emotional needs of a parent and/or sibling. (Hooper, 2007b, p. 323)

Generally, there are two types of parentification

- Emotional parentification happens when the child becomes the parents’ counselor, confidant, or emotional caretaker. Sometimes, this involves a form of ‘Emotional Incest’, where the child is being treated as an intimate partner to the parent. Perhaps the parents were unhappy in their own marriage or dissatisfied with their lives. They might tell the child about their frustrations, cry excessively, complain about their relationships or even hurt themselves in front of the child. Whatever it is that they share with the child, it is too much for their young psyche to handle.

Emotional parentification often occurs in families where one or both parents suffer from mental illnesses, such as depression. It can also stem from the parents’ own attachment difficulties and transgenerational trauma (Aldrige, 2006).

- Instrumental parentification is when the child engages in ‘functional responsibilities’, physical labor, and support in the household, such as housework, cooking, cleaning, taking care of younger siblings, taking themselves to the doctors, and other ‘adult’ responsibilities. This is common in households where one or both parents are incapacitated in some way, for example, due to an injury or illness.

Some of the situations that parentification can arise from include:

- Divorce

- Parents’ Immaturity

- Having unavailable or depressed parents

- Parents’ attachment trauma or attachment difficulties

- Death of a parent or sibling

- Alcoholism or drug addiction of one or both parents

- Chronic disease or disability of one or both parents or a sibling

- Mental illness in a parent/parents or sibling

- The physically abusive relationship between parents

- Physically or sexually abusive parent/child relationship

Some other contextual risk factors include: Having a mother who has been sexually abused, general poverty, low socio-economic status, and divorce (Earley & Cushway, 2002; Macfie, McElwain, et al., 2005).

Is Parentification Abuse?

Is Parentification Abuse? Yes, it can be. It is a form of mental abuse and boundary violation.

Unlike physical abuse, parentification is invisible and, therefore, more toxic and insidious.

Often in parentification cases, the child’s home life is punctuated by horrific tasks, like preventing an addicted parent from overdosing or protecting their siblings from violent outbursts. Exposure to situations like these erases the joy of what should be a carefree time in a child’s life.

In parentification, one or both parents are unable to cope with what it means to be a parent to their child. The parentified child takes over the caretaking responsibilities for a sibling or even the parents themselves, becoming the caretaker, mediator, and protector. In many instances, the parentified child feels as though their siblings or their parent cannot survive without their help. This creates a huge emotional burden that can follow one for life.

The parentified child may have immature and emotionally limited parents. Some of them may have mental illnesses such as Borderline Personality Disorder. The parents are unable to love the child the way they need to be loved. This is a controversial statement in our culture, yet acknowledging reality could be the most bitter yet powerful medicine for our souls.

Mature parents can love their children with liberal and consistent love and attention, emotional openness, allowance for mistakes, and playfulness, as well as act as models for virtues such as courage, empathy, temperance, and compassion. In contrast, immature parents may be emotionally unstable, punitive, controlling, and unable to separate their projections, desires, and wishes from their parentified child’s life.

Immature parents are not ‘bad people,’ but simply children living in adults’ bodies, and therefore have limited capacity. They may do their best but still be unable to offer us what we need as children sufficiently.

If you were a parentified child, you could be traumatized even when no one has actively done anything physical to harm you. It is an invisible pain that hurts the most.

It is not about what was said but what was not said to the parentified child— the praise, the affirmations, the positive feedback.

It is not what was done but what was not done to the parentified child— the absence of physical presence, quality time, intellectual stimulation, meaningful conversations, family rituals, fun, and games.

There might not have been any explicit trauma, but on a level deep inside, the parentified child did not feel welcome in the world.

When we have immature parents, parentification is inevitable.

The parentified child is the counselor, confidant, problem-solver, emotional regulator, and the one everyone counts on. Sometimes, they even took on the role of a scapegoat. They were given all the responsibilities but none of the power.

But regardless of how mature they might have been or acted, the parentified child is still a child. Being burdened with excessive responsibilities sets a toxic trap; the parentified child believes their failure caused bad things to happen to the family, planting the seeds of guilt and shame that they carry into adulthood.

Parentification and the Highly Sensitive Person

Sensitive, gifted and empathic children are particularly prone to be parentified, especially when they have experienced empathic failure from a parent with autism or emotional instability. This is not because the adults maliciously try to harm the child, but because the highly sensitive child intuitively picks up on emotionally unsafe and unstable conditions and takes it upon themself to provide care and support for the family. This can eventually lead to an overwhelming sense of anxiety about the needs and feelings of others and, eventually, an early advance into maturity that equates with a ‘lost childhood’.

Being robbed of their innocent childhood, the parentified child grows up to become adults who have a gap in their psyche. They bury anger, resentment, and grief, which may burst out at unexpected times, affecting their ability to be close to someone, sustain a career, and feel stable. They may resort to filling the void in their souls by ways of substance abuse, avoidance responses in relationships, and other short-term self-soothing strategies.

The harsh reality is amplified to the extreme while a significant portion of their most formative developmental is, essentially, removed.

Abuse is never deserved, it is an exploitation of innocence “ ― Lorraine Nilon

Is Parentification Trauma?

Is Parentification Traumatic? Yes, most of the time, it is. Whilst it may come with some upsides, mostly the deprivation the parentified child experiences has a negative and pervasive impact.

The wounds a parentified child suffers in childhood — especially psychological ones — can last a lifetime. The wounds can affect their everyday lives, underscore their relationships, and undermine their ability to lead happy, fulfilling, and productive life.

After having been parentified, even when the children are removed from the original situation, the trauma remains. Psychological or mood disorders and even chronic diseases can occur as a result.

Research has found that when parentified child internalizes their pain, they may have depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms such as headaches (Earley & Cushway, 2002). If the parentified child externalises their pain, they may become aggressive or even violent (Macfie, Houts, et al., 2005). Research has also found that parentification is linked to interpersonal difficulties (Macfie, Houts, et al., 2005), and bad academic performance (Mechling, 2011).

The roles in the family were reversed in the first place because it was not safe for the parentified child to act age-appropriately as their child-self in the relationship. If they were to bring their needy, vulnerable child out to their parents, hoping and yearning for care, they would be disappointed, traumatized, and hurt.

So, from the get-go, the parentified child learned that the only safe thing to do was to rise above their pain.

They might have been angry, but the only solution they knew was to suppress that emotion.

They might have been depressed, but all they could do was hide it and soldier on.

It was never a conscious choice the parentified child made, but suppressing their feelings was their only option. This need to dissociate from their inner experience, however, creates a psychic split in them. A part of the parentified child goes on with life as the ‘Apparently Normal Self’, acting stoic, stable, and strong. However, their ‘Traumatised Self’ remains buried deep within, and their rage festers unconsciously. Later in life, they may feel haunted by their trauma symptoms without knowing why. (Here is an article about the Trauma Splitting that we experience as a part of Complex Trauma)

Therefore, even as a grown-up, the once-parentified child struggles to play, be spontaneous, relax in intimacy, trust their instincts or other people, and they ultimately feel that they are only living a partial life. They may be stuck in a half-dissociated state where they watch life goes by without being in it. They are disconnected from their sense of vitality, joy, and passion.

“Trauma… does not disappear if it is not validated. When it is ignored or invalidated, the silent screams continue internally heard only by the one held captive.”

“Trauma… does not disappear if it is not validated. When it is ignored or invalidated, the silent screams continue internally heard only by the one held captive.”

― Danielle Bernock

Parentification Trauma: Turning Against Yourself

The classic symptoms of chronic childhood trauma, or Complex PTSD, are shame and guilt. This is a result of what the parentified child has carried forward from their childhood.

As children, it was very difficult for us to be angry at our parents, even if they had hurt us and let us down. Admitting that our parents were neglectful or abusive was a life-threatening prospect, for they were the only people we could depend on.

If we knew our parents could not tolerate disobedience or that we would be punished for creating conflicts, it ‘made sense’ for us to blame ourselves rather than risk confronting them. We dared not be critical of the authority figures whose goodwill was essential to our survival, so our young minds preferred to deny our pain. This results in the psychodynamic process of ‘turning against oneself’, where we redirect anger and resentment for others internally toward ourselves. We started to interpret mistreatment as our fault or something we deserved. Our righteous indignation became internalized guilt and shame.

Self-blame is also related to our need to feel in control. More terrifying than anything else in this world is the feeling of complete powerlessness in an unpredictable, precarious universe. Even to adults, this is an existential threat, let alone to children.

To evade such horror, we resorted to the conclusion that it was our fault that bad things happened. We would rather believe we had done something to make it happen — because we were not good enough or that we didn’t do what we could. We thought that we would not have been hurt if we hadn’t expected, hoped too much, and trusted so much. Self-blame explains the unbearable injustice that occurred; somehow, it was more tolerable than the alternative — that the people we trusted had betrayed us or that the world is a hostile place. As psychologist Fairbairn said, ‘It is better to live as a sinner in a world created by God than to live in a world created by the devil’.

Parentification as a Transgenerational Trauma

Emotionally under-developed or immature parents believe that they have done their absolute best, though deep down, they know it has not been enough. They may be plagued by unconscious shame and guilt, but ironically take it out on their children in the form of emotional abuse, guilt-tripping, or excessive control. Others may resort to excessive material provisions for their children.

We may look like we are loved based on what can externally be seen, yet inside we feel like orphans. If we dare let our truth leak out into the world, we are punished for being ungrateful and demanding. So, we have no choice but to bury our truth within a facade of normalcy.

Many of us become stuck in a toxic dynamic because of our family’s conscious or implicit investment in denying the problem. It is easier for them to stay blind to their shortcomings and to discharge responsibilities. Even as adults, our parents inability to own their flaws leaves us in a place where we are being tripped over and ignored every day, but there is never an apology.

In her book For Your Own Good Swiss psychologist, Alice Miller coined the term ‘Poisonous Pedagogy’ to describe a mental control device some families use to maintain a position of power and to normalize a dysfunctional dynamic. ‘Poisonous Pedagogy’ consists of a list of doctrines that are passed on from generation to generation. Here are some of them:

- Parents deserve respect simply because they are parents.

- Children are undeserving of respect simply because they are children.

- Obedience makes a child strong.

- The body is something dirty and disgusting.

- Strong feelings are harmful.

- Parents are always right.

- Parents are creatures free from drive and guilt.

- Duty produces love.

- A high degree of self-esteem is harmful.

- A low degree of self-esteem makes a person altruistic.

- Severity and coldness are good preparation for life.

- A pretense of gratitude is better than honest ingratitude.

- The way you behave is more important than the way you really feel.

- Neither parents nor God would survive being offended.

(For Your Own Good, pp 59−60)

According to Miller, these doctrines are how psychological trauma is transmitted from one generation to the next. Research has hypothesized that exposure to these Pedagogies negatively affects a person’s personality development.

In recent research, it has been found that parentified mothers are more likely to emotionally parentify their own children based on their own internalized experience as a child (Hopper 2007).

It has also been found that transgenerational transmission of parentification trauma is more prominent when it comes to mothers as compared to fathers. In other words, mothers’ unconscious ideas of parenting have a greater effect on the child attachment development.

“When you can identify the insecurities inside the person that is hurting you then you can begin to heal. It isn’t about you. It is about their past.”

― Shannon L. Alder

Can Parentification be Beneficial?

Can parentification ever be a beneficial thing? Yes, it can be in some ways. As reviewed, most of the time parentifcation is abusive and traumatic. However, in some ways, it can be beneficial to both the family system and the parentified child.

Parentification might have been necessary for the family system to sustain itself. For example, it was with parentification that the child has kept the depressed parent alive. Or, it was with parentification that the younger siblings were protected from the violence of the alcoholic parent. Parentification trauma comes with a huge cost to the parentified child, but it might have been the only way the family as a whole could be protected.

Parentification might have also been developmental in some ways. Unless it is excessive, when a child performs chores or occasionally support their parents, they could experience their own strengths and abilities, and grow and learn from that (Boszormenyi-Nagy & Spark, 1973). If only Instrumental parentification took place, instead of severe emotional parentification, it is possible that a child could accomplish a sense of accomplishment and sense of agency through taking care of affairs at home (Aldridge, 2006).

Parentification can also help a child develop more empathy and greater interpersonal competence. If the parentified child is able to work through the impact of parentification and heal from their trauma through robust personal development, they could come out the other end with more resilience, and self-awareness. They can be highly empathic to others whilst remaining differentiated (The way psychologist Bowen defines it).

Parentification Was Once a Survival Mechanism

To survive in a home with immature parents, we have adopted various strategies based on our personalities and the resources that were available, but the impact of parentification carries on beyond childhood.

Some of us made jokes and became the comedian in the family. Now we don’t know how to be vulnerable to others without the disguise of humour.

Some of us became extra compliant, hoping that by being an ‘easy child’ we would be loved. We came to believe it was our duty to serve, help and rescue, and this pattern continues into our adulthood, when we become people-pleasers and unable to set boundaries.

Some of us left home early to pursue our freedom, but the trauma never left us. We may become wary of relationships and fearful of engulfment, so we isolate ourselves and push away love and intimacy.

Some of us shouldered all responsibilities diligently and became perfectionist adults who are unable to release control or relax. If our parents were not just unavailable but also emotionally volatile, we would also have trained ourselves to become hyper-vigilant, always watching out for signs of upset or anger in the people around us.

We may blame ourselves for everything that goes wrong, assuming responsibility for other people’s dysfunctions or misfortune. We constantly try to fix things and even neglect our own needs while trying. When things do not go the way we want them to or when we make the slightest error, we drown in cycles of guilt and shame.

The impact parentification trauma we carry depends on a myriad of factors, part nature, part nurture:

If your parents tended to praise you only for what you did and not for who you were, your internalized inner critic would always be evaluating your success. Rather than allowing you to just ‘be’, you are pushed to be a ‘human doing’. The only way you know to survive in the world is to work hard, to achieve the next credential, and never to slow down. You live according to metrics and standards set by society rather than your spontaneous true self. Your patterns leave you empty on the inside, and from time to time, you wonder if you are acceptable without something impressive to show.

If your parents were depressed and relied heavily on you for love and comfort, you would have learned to define yourself through the eyes of others. You feel ungrounded, as though the center of gravity lies in other people and not in yourself. While you are highly empathic and attuned to people’s needs, you lose touch with your own needs. You may feel you are constantly trying to earn love from those around you, and yet however helpful and loving you are, people may not reciprocate. When they don’t, it hurts deeply.

If you were overburdened with responsibilities as a child, it is likely that you have become highly sensitized to errors, imperfection, and unfairness in the world. You have a harsh inner critic inside of you, constantly telling you that you are not doing things correctly or perfectly enough. You live with constant pressure to fix things, correct things and make things right again. Being highly judgemental and critical, your inner critic also comes between you and those you love. Those around you feel scrutinized and pressured, even if you do not mean to make them feel that way.

If your parents have emotionally or physically abandoned you, you may, for your whole life, feel like an orphan spiritually. You feel misunderstood and alone in the world, unable to fit in. Your inner critic derails your self-esteem by comparing you to others, telling you they all have a happier, more ‘normal’ and fulfilling life.

If your childhood environment were unstable and unsafe, you would have been deprived of the opportunity to cultivate trust in the universe. Doubt and fear become your primary habits. Rather than taking productive action, you are often held in ‘analysis paralysis,’ making a long list of ‘what might go wrong’.

Always vigilant and watchful, you scan the environment for threats or danger.

If your parents were bullies, you would have learned to survive on power and assertion early in your life. You see the world as a dog-eat-dog place, and it is risky to let your guard down. It becomes impossible to reveal your vulnerabilities to anyone or to let people in to help and comfort you. You are ‘allergic’ too soft emotions such as sadness and neediness. You have put up a wall to keep you safe, but it also keeps you in isolation. Even if you have achieved power in the world, you feel incredibly alone.

“Adulthood is an attempt to become the antithesis of the wounded child within us.”

― Stewart Stafford

How Do I Move on From Parentification Trauma?

Despite the horrific impact of parentification trauma, healing from it is possible. Adults who have been parentified are highly sensitive, empathic, kind, and intuitive. In a way, those who were once a parentified children can become gifted parents because they have been doing it since they were young.

Therapy or coaching aims to start prioritizing your needs before you jump into rescuing or pleasing others. You might have been a skilled parent figure to others all your life, but now it is time for you to parent yourself. As a child, you needed love and attention to be listened to. You also needed room to play, make a mess, and freely explore the world without being burdened with responsibilities. If you were deprived of these in the past, reclaiming your lost childhood is now within your power.

The first step to healing is to tell your story of being a parentified child as it is. You might have spent years trying to hide or deny the truth in order to protect yourself and your family. Perhaps you have few memories of your childhood or find yourself hitting a wall of emotional numbness when you search within.

When someone asks you about your parents, you are unable to speak negatively of them. You may even feel guilty for not having been a ‘happier’ person, given everything on the outside seemed ‘fine’ in your childhood.

Since the trauma you experienced was mostly invisible, you have difficulty gaining recognition for the trauma you have endured.

But the insidious nature of your trauma does not make it any less valid. Acknowledging the reality of your lost childhood, however painful at first, is the first step to healing. You begin to grieve the childhood you deserved but never had and can make room for healthy and justified anger. Without this step, you will continue to expend energy in denying, suppressing, and rationalizing your past, which blocks the healing process.

In this delicate and potentially precarious process, compassion is essential. Before we generate compassion for anyone else, however, we must learn to cultivate self-compassion. Self-compassion is a relatively new concept in Western psychology, whereas self-contempt is a common trait in western culture.

Having been parentified, your automatic default is to assume things are your fault. Your inner critic constantly tells you that you are not doing enough or good enough, and that when bad things happen, it is your job to mop up the consequences. As you spiritually mature into becoming your own person, however, the time comes to put things right and to say no to your internalized bully.

But we do not hate our ‘adapted self’ who is perfectionistic, highly anxious, and trapped in people-pleasing ways.

Our defensive mechanism forms an honorable part of us. We can greet it, bow to it, thank it. We say: ‘Thank you for your service, my brave soldier. I now know what to do, and finally, you can relax and rest.”

Then we turn to the child in us that has been neglected. We say: ‘I am sorry about what you had to go through. I am sorry no one was there for you when you most needed someone to stand up for you.’

To the sad, lonely, wounded one in us, we say: ‘I am sorry. Please forgive me. Thank you. I love you.’ Then, we repeat in the gentlest, most compassionate whisper, again and again: ‘I am sorry. Please forgive me. Thank you. I love you.’ (Hoʻoponopono)

You may make a list of people who have loved and supported you, then close your eyes and imagine them forming a circle around you. Allow your body to soak in the feeling of being loved.

If you have little experience of genuine support in life, contemplate what you might say to a person or a child you love. Imagine holding a vulnerable person in your heart, and experiencing the tenderness. Then, see if you can direct those tender feelings toward yourself.

You deserved to be unconditionally loved for who you were, not for what you did or how you looked to the outside world. You were a completely innocent being, birthed into this world from the universe. Even if your childhood was nauseatingly painful and full of holes, it is never too late to give yourself the childhood you deserve.

“Our parents cannot love us the way we need them to.” Acknowledging this truth involves us courageously processing challenging emotions such as deep grief, anger, and hurt. But these feelings are temporary if we don’t block them. If we know that we are on a path toward liberation and allow these feelings to go through us, we will be liberated and rewarded with freedom in the end.

Inner peace and tranquillity might be the highest form of joy. Doing the emotional work to heal our childhood hurt and transcend the wounds created by our parents is an essential path to attaining that joy. If we never transform our wounds, then our anger, guilt, and shame triggers will always lurk in the background, catching us off guard, sabotaging our relationships, and blocking our creativity. Only when we can walk the courageous path of seeing the truth can we get to the other side of it.

Our childhood wounds do not block our path towards happiness and freedom; they are the path.

This article is written by Imi Lo.

If you prefer audio input:

Imi Lo is an independent consultant who has dedicated her career to helping emotionally intense and highly sensitive people turn their depth into strength. Her three books, Emotional Sensitivity and Intensity, The Gift of Intensity, and The Gift of Empathy, are translated into multiple languages.

Imi holds three master's degrees in Mental Health, Buddhist Studies, and Global Cultures, alongside training in philosophical counseling, Jungian psychology, and other modalities. Her multicultural perspective has been enriched by living and working across the UK, Australia, and Asia, including with organizations such as Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders and the NHS (UK). Throughout her career, she has served as a psychotherapist, art therapist, suicide crisis social worker, mental health supervisor, and trainer for mental health professionals.

You can contact Imi for a one-to-one consulting session tailored to your specific needs.