Table of Contents

Signs of Quiet BPD — Are You Suffering In Silence?

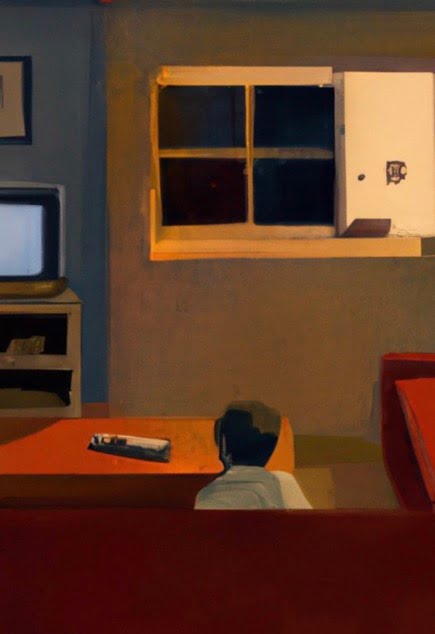

Quiet BPD looks different from ‘typical’ BPD. Having Quiet BPD means you ‘act in’, rather than act out. You may not have stereotypical BPD symptoms such as frequent anger outbursts – instead, you suffer in silence. You may appear calm and high functioning, instead of ‘exploding’, you implode and collapse from within. Your arms and legs may be covered with scars, but you hide them. Your heart is close to breaking, but you never want to burden anyone around you.

While there is now more awareness about BPD, most people don’t know that BPD manifests itself in different forms. It is not that there are four ‘different groups of people’. Instead, these categories describe different ways of coping with an incredibly painful condition— some people fight, some people flee, and some people dissociate. It is a matter of spectrum, rather than categorization. No one has either completely ‘classic’ or ‘quiet’ BPD or should be labeled as such. As we discuss ‘quiet borderline’ or Quiet BPD, please be mindful that it is a survival strategy, not a definition of your personality.

―

What is Quiet BPD?

‘Quiet BPD’ is not an official term in the DSM, and there are various ways of understanding it. The following is a synthesis of what I can find in the literature and my own conceptualization. It is based on existing research, theories, and my clinical observations.

The stereotypical image of BPD is that it involves ‘dramatic behaviors’— anger outbursts, big arguments with partners. These characteristics describe someone who ‘acts out’. Having Quiet BPD, however, means you ‘act in’. You feel and struggle with all the same things— The fears of abandonment, mood swings, extreme anxiety, impulsiveness, and black and white thinking (splitting); but instead of ‘exploding’, you implode. You may not have frequent anger outbursts, but you internalize your painful emotions and struggles. The aggression or irritation is directed towards yourself.

When you are triggered, rarely do you lash out at others, but you go into isolation and engage in self-injurious behaviors. You may not act impulsively, but when you reach a breaking point, you still engage in self-harming or self- sabotaging behaviors of different forms. Your arms may be covered with scars from self-harming, and you hide them.

Deep inside, you may feel that your emotions are wrong, you are ‘too much’ for others, your existence itself is a burden, or you don’t deserve a place in the world. You would rather be in pain than affect other people, so you hold everything in.

People with Quiet BPD tend to have an avoidant attachment style; many have comorbid Avoidant Personality Disorder traits. Instead of other reactions like ‘ fight’, ‘flight’, you’ freeze’ in the face of trauma and pain.

Quiet BPD is more dangerous than the classic form of the disease because it’s tough to fathom the emotional distress inside you. When you have emotional needs, you tend to numb out or dissociate. Instead of seeking help, you withdraw from those who care for you. Even if they try, you do not allow them to help you. Built into Quiet BPD is the ability to tolerate distress and avoid outwardly expressing their needs. This keeps you in a loop of quiet suffering for a long time.

Research shows that many people with BPD get better as they grow older (Zanarini et al., 2010; Abrams & Horowitz, 1996). This, however, does not apply to people with Quiet BPD. This is because you have less dramatic symptoms and do not cause any concern for those around you. People around you do not usually know you are suffering and are less likely to offer help or feedback.

Do You Have Quiet BPD?

When you are upset, is all the shame, hate, or anger directed towards yourself?

Do you often find yourself thinking, “I must have said or done something wrong,” or “I must have been at fault”?

Do you have a high need for control and don’t know what to do in situations where there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’?

When someone upsets you, do you withdraw from them without having first trying to speak to them?

Do you deep down believe your very existence is a burden to others?

Do you mentally dissociate and feel empty and numb?

Do you live in denial of the anger you feel? Perhaps to the point where you don’t know how ‘anger’ feels anymore?

Do you spiral into crushing depression or tend to isolate yourself at the slightest mistake you feel you have made in your interactions with people?

Are there incidences where you have cried for days, stayed in bed, and remained unmotivated without anyone knowing?

Darkness comes. In the middle of it, the future looks blank. The temptation to quit is huge. Don’t.

– John Piper

Why is Quiet BPD so Painful?

Here are some specific symptoms that characterize Quiet BPD:

You are Calm on the Outside but Suffer on Inside

Due to an innately hypersensitive nervous system and/or the Complex PTSD you might have experienced, you constantly live with low-grade anxiety, which can escalate into a panic when triggered by particular stressors. However, no matter how much you are struggling, you are likely to downplay or hide your distress and put on a stoic facade to the outside world.

Perhaps deep down, you do not feel you deserve time, attention, and care from others; Perhaps when you do show your vulnerabilities, you are plagued with guilt and shame, so you would rather hold things in. As time goes by, you become good at camouflaging— saying what others need to hear and presenting yourself in a socially acceptable way.

You may be feeling a lot on the inside, but most of the time, you would hide it from others. Sometimes, you even hide it from yourself. Thus, you appear flat and unemotional. This is very different from the ‘dramatic’ expression someone with ‘classic BPD’ may exhibit. People think that you are doing well, and may not reach out as you struggle in isolation.

You may also suffer from what is known as Alexithymia—the inability to recognize or describe emotions. Research has found that people with BPD are highly responsive to other people’s feelings and can feel other people’s pain as their own, but since they do not have the language to identify and express these feelings, they come across as unempathetic. (New A.S. et al., 2012)

Since you do not have the language to channel your pain, you ‘express’ your anger and hurt through a series of self-destructive behaviors including alcohol or drug abuse, binge eating, compulsive stealing, reckless driving, etc.

You Have a High Need For Control

In general, you crave structure and order. You prefer things to be planned and would want to avoid uncertainty and unplanned risks in life. When something unexpected happens, you feel thrown off balance; even when they are ‘good’ things, you feel suspicious of them. Because of your need for control, you may have many written or unwritten rules that govern your life. This creates a kind of rigidity that limits creativity, playfulness, and spontaneity.

You may be uncomfortable with situations where there are no rules or instructions. You prefer things to be predictable, and controllable, and that you can always get the confirmation you are doing the ‘right’ thing. Therefore, you may find social situations and unstructured activities exhausting, because you never know what to do or say.

This need for hyper-control can affect your willingness to engage in therapy too. If you meet with a therapist who leaves the session relatively free-flow, asks little questions, or does not give you specific activities to do, you may feel lost and uncomfortable. You try to do or say the ‘right’ thing but your therapist neither approves nor disapproves. You may even blame yourself for not using the session well afterward. (This does not mean the therapy is ‘bad’ or not working, but it is worth sharing how you feel with your therapist. Hopefully, they will have an understanding of Complex Trauma/ CPTSD and the inhibition defense that comes from that. Together, you can hopefully slowly get used to taking up space for yourself, and trusting your organic expressions, rather than relying on external directions)

You may also choose to avoid an intimate relationship. That makes sense, as relationships inevitably involve exposing your vulnerability and being subjected to factors you cannot control.

(For more on Overcontrol as a trait, please refer to this page,or this interview.)

You Withdraw From People

Compared to people with ‘classic BPD’, you are more likely to have an avoidant attachment style rather than an anxious attachment style, which also means you may abandon relationships easily— with therapists, partners, and friends— whenever conflicts arise.

You may engage in a common BPD symptom called’ splitting’— where people become either ‘all good’ or ‘all bad’, or when you go from intensely loving someone to hating them. When someone offends or hurts you, they become someone you hate (all bad). In quiet BPD, instead of confronting them or bursting out in rage, you shut down. You may disappear, ignore the offender, unfriend them on social media, or give them the silent treatment. If you don’t give others a chance to explain or to try and mend the relationship, they may not even be aware of what has happened. As a result, you might have lost friends and feel aggrieved and isolated.

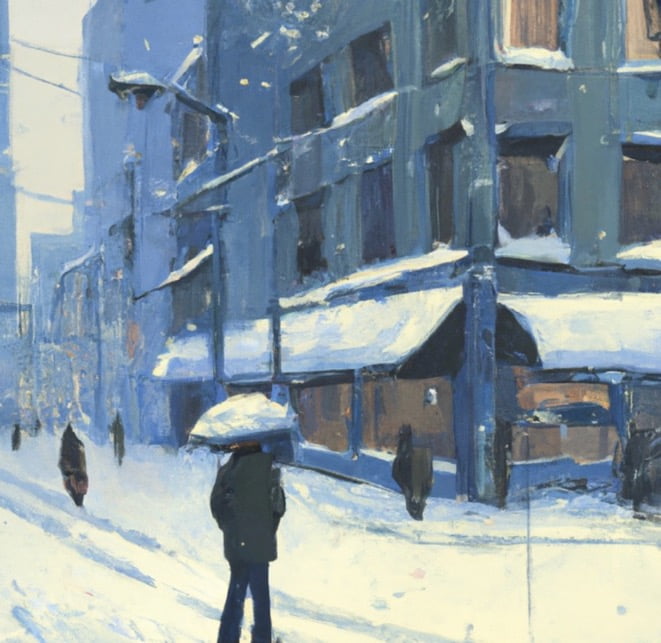

Socially, you feel as though you are sleeping on a bed of nails. As much as you would like to engage, being around others fuels your self-doubt and anxiety. Disagreements at work, an indication that your partner is unhappy with you, or if your parents compare you with someone else, can push your buttons to an extreme degree. Eventually, you would rather socially withdraw to avoid shame and emotional storms. You become increasingly disconnected from the world.

―

You Mentally Retreat or Dissociate

Because avoidance is your primary coping mechanism, you avoid not just social situations but also your inner world. You tend to shut down when feelings get overwhelming. When you dissociate, you become empty and numb.

You may experience depersonalization and derealisation, where you feel out of touch with reality, like you are observing yourself from the outside, or experience reality as unreal. When things become stressful, you run your life on autopilot while feeling nothing on the inside. Not just emotionally, you may also feel physically numb, unable to taste or sense anything. You feel like you are living in a movie or a dream, or are living someone else’s life. You might have forgotten a big part of your life story and suffer from partial amnesia, not able to string together a coherent narrative of your life.

Because of your disconnection with the inner emotional world, you may have incongruent and odd expressions at times. For example, you may compulsively laugh or smile when you talk about something distressing. Even if your friends or therapist point that out, you cannot seem to help it. Or, Even when others show deep empathy for the trauma you have gone through, you are not able to feel anything or show signs of upset.

You Have an Unclear Sense of Self

As a result of the disconnection with yourself, you also do not have a robust ‘sense of self.’ This means you generally have a low awareness of your own emotions, desires, motivations, and needs.

Emotions are there to signal us what we need; but if you have been severely neglected or abused, you might have learned to shut them down. If your experience has taught you that there is ‘no point in knowing your needs, for they will never be met, you would of course find it easier if you are no longer aware of your needs. After all, continuing to be made aware of our needs and not having them met is a painful state to be in. But when we shut down our emotional system, we face many other consequences. For one, the way it works is that we cannot only shut down negative feelings. When we attempt to shut down our feelings of neediness, anxiety, and anger, we also stop feeling joy, love, and a sense of fulfillment. You may end up living life on auto-pilot as if you are watching it go by without being in it.

Without a solid sense of self, you may have ever-changing ideas about who you are, what you are doing, or where you are going in life. You want to feel like you belong somewhere, but at the same time find it is difficult to commit to an endeavor. One minute you are totally into a person, a social movement, an idea, or a belief system, and the next moment you lose interest in them. With constant changes in your relationships and career, it is difficult for you to establish a sense of stability for optimal mental health.

Self-blame and Self-sabotage

Many with Quiet BPD have a tendency to blame themselves even when it is not their fault. You may have an underlying sense of dread that your presence is a nuisance to others. You may ruminate a lot and go over interactions in your mind, only to harshly scrutinize what you had said or done.

You tend to shoulder too much responsibility for conflicts or arguments in a relationship. Even if you were abused, you may blame yourself rather than direct your anger towards the people who have hurt you. You may also have a tendency to over-apologize for things.

Always blaming yourself contributes to low self-esteem, which can also result in a tendency to self-sabotage. For example, having a good relationship or working at a job where you are appreciated fills you with uneasiness. You doubt yourself and deep down do not feel you deserve to have good fortune, appreciation, and love. You would rather turn away joy than later be disappointed. Therefore, you push away opportunities and hope. This pattern stops you from reaching your full potential.

You Avoid Conflicts and Anger at all Costs

A lack of emotional validation is at the core of the BPD wound. It makes sense, therefore, that you would want to seek from your partner or those who are close to you what you have wanted all your life but could not get. You may be constantly trying to make ‘everyone’ happy. Perhaps you put an excessive amount of time and effort into being a mediator, confidant, and peacemaker. Or you are unable to say no, even if it means sacrificing your own needs. You may do anything just to avoid conflict and anger.

When you get emotionally attached to someone, you sensitively hang on to their every word and action, constantly trying to decipher if they like you or care for you. Even at the slightest hint that someone might be upset with you, you feel your world start to crumble. You become incredibly anxious about potential rejection if friends or partners don’t keep plans or return your calls.

Because you are afraid of conflict, you are always editing and checking yourself to make sure you never offend anyone. You may feel rigid, contrived, and not able to enjoy friendships and relationships in a carefree way.

―

You Fear Both Abandonment and Intimacy

The stereotypical image of someone who has BPD is that they are clingy and needy. A person may fight, beg and cry to stop imagined or actual abandonment. The fear of being left behind causes chronic anxiety, panic attacks, and hyper-vigilant physiology. In terms of attachment patterns, these behaviours relate to the anxious-ambivalent attachment style.

However, with Quiet BPD, your fear of abandonment may titrate with an avoidant attachment pattern. (Or, you may deep down be anxious-ambivalently attached, but in terms of behaviors, you act with avoidant tendencies.)

You do not only fear abandonment but also fear intimacy. You may avoid relationships altogether, or you may avoid exposing yourself. The moment a romantic partner comes close to knowing the real you, you find a reason to break things off. Convinced that you would eventually be abandoned, you would rather end the relationship before it ends on you. When you feel anxious in a relationship, you are more likely to withdraw rather than raise conflicts, which hinders you from building lasting and fulfilling partnerships.

Your ‘High Functioning‘ Facade Keeps You In Deeper Isolation

It may be due to your childhood or social conditioning that you have developed what psychologists call a ‘false self’. You hold up a ‘happy, successful, and normal’ image even when you are paradoxically crumbling on the inside.

You are likely highly driven and perfectionistic. You have a tendency to compulsively ‘fix things,’ both in your career and personal life. You may obsess about finishing a task even if that means you have to sacrifice rest or the quality of your relationships. Your perfectionistic tendencies are by and large rewarded by society and might have brought you many career successes.

You set very high standards for yourself and others; you work hard, but get frustrated when others underperform or don’t follow rules. You are highly disciplined, and most of the time you keep things under control. Most of the time, you don’t really need or want others to tell you what to do. Because of your appeared competence, you can come across as being aloof or dismissive of input from others.

You maintain a facade of perfection and keep up with your external achievements, because somehow somewhere, you feel that you are not fundamentally and inherently worthy of love. You trade your time for recognition and your soul for external approval. As you hide behind the socially successful persona, others do not get to know the real you and do not see that you need help. This leaves a void in your heart, and the pain of not living a full life will eventually erupt.

We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.

Martin Luther King Jr

The Psychology of Quiet BPD— Anger Turned Inward

At the core of Quiet BPD is a thwarted relationship with anger, where instead of giving anger a healthy channel to be expressed, you have learned at some point in your life to turn it inward towards yourself.

Since the Freudian era, psychoanalysts have understood depression to be aggression that has been (mis)directed inward. Such an act, albeit mostly unconscious, is what depletes a person’s life force and energy, causes toxic shame, low self-esteem, people-pleasing tendencies, and self-destructive urges.

Usually, this mechanism is developed out of the need to survive a childhood where our primary caregivers had been cold, critical or dismissive. Due to their immaturity, mental illness, undiagnosed neuro-atypical traits (such as autistic spectrum, Asperger’s or ADHD), extreme work or health demands, your parents might not have had the capacity to emotionally ‘hold’ you. Instead of acting as a safe provider for many of your infantile and childhood needs, they were put off when you sought attention and perhaps avoided touching or playing with you. Or, they were physically present but emotionally blank. They might have reacted contemptuously to your call for connection and condemned you for being ‘too much’.

As a child, being needy was your way of expressing love and seeking connection from others. However, if your parents were easily overwhelmed and responded to your needs with impatience, frustration or even disgust, you may fail to internalize a sense of fundamental worthiness.

Some parents are afraid of conflict or intense emotions. When you cry or are frustrated, they panic, and in turn, punish you for what they feel. If your parents responded to your anxiety by escalating the situation or becoming hysterical, you would receive the message that your presence was a nuisance or even a threat. They may have been so emotionally volatile that they were hardly able to contain their own anger and distress, let alone yours. As a sensitive and empathic child, it would soon become apparent that any intense emotions, especially anger, were unwelcome. Therefore, the only choice you had left, was to turn any frustration you experienced towards yourself. It was safer to drive all blame onto yourself than to risk losing attachment and love from the people you depended on. There was nothing you could have done to control people who were more powerful than you, so all you could do was carefully monitor yourself, and use self-blame as a way to make sure you don’t overstep. This unconscious survival strategy creates a set-up for Quiet BPD: Not only was your trauma invisible, but you were also trained to remain silent about it. The way you learned to preserve a relationship was through being an anxious subordinate.

Although this mechanism might have been necessary when you were a small, dependent child who had to cope with emotionally volatile parents, it is not sustainable and creates other psychological turmoil later in life. As Freud put it: “Unexpressed emotions will never die. They are buried alive and will come forth in uglier ways”. The trauma you held in your body and psyche would eventually erupt, resulting in a myriad of self-destructive Quiet BPD symptoms such as chronic self-isolation and self-harming.

“She was a stranger in her own life, a tourist in her own body.”

“She was a stranger in her own life, a tourist in her own body.”

―

Emotional Detachment and Quiet BPD

Quiet BPD is not something you should blame yourself for. Perhaps, see yourself as someone whose heart has been shattered by the pains of trauma, leaving you a mere shadow of your authentic self. Whether it’s the loss of a loved one, the sting of betrayal, or the tumult of a broken relationship, these experiences have left your inner core self feeling vulnerable, fearful, and uncertain. In response, you have no choice but to withdraw from yourself, others, and any potential relationships.

Another common characteristic of Quiet BPD is emotional detachment, where you are not truly living but simply ‘existing’ in a desolate state, depriving yourself of emotional intimacy and closeness. Despite a profound desire for connection, fear impedes your ability to reach out for one.

Perhaps, at the core of Quiet BPD lies a deep-seated fear of vulnerability and the potential for further hurt. This fear is so potent that it entraps you in a no-man’s land – unable to reach out to others for fear of being hurt, yet also unable to connect with your own emotions for fear of losing control. Consequently, you had no option but to fortify your heart, shielding yourself from the warmth and tenderness of close relationships.

Due to your relational ambivalence, what you do in relationships—the push-and-pull—may be perplexing for both yourself and others; you may reach out for connection in small ways only to quickly retreat into your protective shell.

A tragedy unfolds when an inherently emotionally sensitive, intense, and gifted soul becomes emotionally detached. They had to dilute their innate sensitivity and deep empathy for the fear of being named as ‘too much.’

This shielding, however, is not a conscious choice but a necessary adaptation for survival.

Emotional detachment is not typically linked to Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), where someone is seen as having ‘too many feelings and too intensely’ rather than a lack thereof. However, what is often underestimated is that emotional detachment or the act of numbing oneself can serve as a coping mechanism in reaction to the overwhelming sense of losing control over one’s emotions. The enduring detachment, however, can be equally incapacitating and distressing as the intense mood swings commonly attributed to ‘classic’ BPD.

Quiet BPD is marked by internalized emotions and shame-driven tendencies. Intellectualizing, rationalizing, and emotional detachment are not immediately apparent to others, so it makes diagnosis challenging. But that does not mean you suffer any less. Instead of intensely feeling everything, like in ‘recognizable BPD,’ you may feel nothing at all (though you may also find yourself rapidly switching between the two states of feeling too much and nothing). Despite outwardly appearing normal, you grapple with feelings of emptiness, loneliness, and disconnection.

Given the growing body of evidence linking BPD to hyper-mirror-neuron activity, it is reasonable to believe that those with Quiet BPD are born with an innate sensitivity and empathy for others. They were once emotionally porous, overly empathic, intuitive, constantly absorbing and feeling the emotions of others. However, this sensitivity can become a double-edged sword when they are exposed to trauma. It can make them more vulnerable to being hurt and cause them to feel the pain of betrayal, rejection, and loss more acutely than others.

In an attempt to safeguard your sensitive core, you may subconsciously construct emotional barriers, resorting to emotional numbing. This process, as articulated by psychologist Winnicott, unfolds as a tragedy – a loss of your “true self” through the suppression of emotions, particularly anger and shame.

Consequently, the once-sensitive and empathic soul turns into an extreme, distorted version, marked by detachment from the profound emotions that were once a source of vitality.

Quiet BPD and Structural Dissociation

Like in High-functioning BPD, Quiet BPD, especially when it comes to emotional detachment, is also linked to a process known as ‘structural dissociation,’ more commonly understood as ‘trauma splitting.’ As a trauma response, there exists a division within your personality into two distinct components – the ‘normal self’ and the ‘wounded self.’

The experience of growing up with parents who couldn’t offer the necessary emotional support has a profound impact on the terrain of your inner world. It’s not the kind of trauma that comes from a single event; instead, complex trauma arises from a persistent absence of empathy and enduring neglect, leaving a lasting imprint on your soul.

As a vulnerable child, escaping the pain wasn’t possible. Leaving wasn’t an option, so the coping mechanism became a psychic withdrawal – not physical, but a hidden and invisible retreat.

Without realizing it, forming this internal “split,” locking away a part of yourself with all the pain and anger, was an essential yet unnoticed act. Even if you don’t remember, that pocket of memory silently exists within you, frozen in time.

Psychologists refer to this unconscious act as “structural dissociation.” It’s your mind’s method of building walls within your psyche, separating pain into different parts to protect you from being overwhelmed by a floodgate of emotions.

It is not that you completely lose touch with reality, as in schizophrenia; and you are still conscious that you are ‘one person’. However, certain triggers — usually those associated with humiliation, abandonment, and rejection— can make you feel taken over by foreign “parts” of yourself, each with its personality, feelings, and behaviors. It is as though you have different characters within you, often acting at a much younger age—a screaming toddler, a raging teenager.

This wounded self is frozen in time at the age of the trauma, mostly concealed but can sometimes be triggered. And when you are triggered, you may experience PTSD-like symptoms like flashbacks, severe mood dysregulation, and anger with no clear reason.

Externally, you may seem to have it together, but in the process, you neglect fundamental human needs – expression, play, spontaneity, intimacy. This neglect leaves you with a profound sense of emptiness as if life lacks meaning or purpose, and you are only watching it go by without being in it.

Psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott introduced the idea of the false self as a protective facade individuals develop to navigate an environment lacking genuine care. While it helps you look and seem normal to others, this false self often leads to immense emptiness and disconnection from your authenticity.

As society rewards how ‘functioning’ you are, you become increasingly attached to the Normal Self. Now your vulnerable parts feel distant, like strangers within you. You become more and more afraid to look inside or to let any pain out. Numbing your emotions as a coping mechanism may work for a while, but eventually, the pain will demand to be felt.

However, constantly suppressing those feelings takes a toll, leaving your tank empty.

You no longer have any life energy or drive to connect with your dream, fuel your passion, and pursue your goals. This perpetuates the toxic cycle where you find less and less meaning and joy in life.

But your past does not have to dictate your future.

Acknowledging the pain, and reaching out to those wounded parts, is the most courageous step you can take right now.

It is saying, “I see you, and I’m ready to face what’s inside.”

It might be the hardest thing you ever have to do, but it’s a journey worth taking for the sake of reclaiming your one chance to live a life where you are finally not just a cold and critical observer, but a joyous, driven participant.

It is what opens the door to truly living.

(For more on Structural Dissociation, please refer to this article on Trauma Splitting)

“Anger is an acid that can do more harm to the vessel in which it is stored than to anything on which it is poured.” – Mark Twain

Healing from Quiet BPD

Do psychiatrists recognize Quiet BPD? What Therapies Are Available?

Having ‘quiet’ BPD puts you in an isolating position because it’s harder for people to recognize that you need help, so it can take much longer to get an accurate diagnosis. Mental health professionals often overlook Quiet BPD when assessing someone who has it. Since you do not display the classic signs of BPD (i.e., anger and explosive behavior), you may be given other diagnoses such as bipolar, depression, anxiety, or Asperger’s syndrome.

Not too long ago, the popular opinion in the medical profession was that BPD was untreatable. Now there are several treatment options, such as psychotherapy, Schema Therapy, Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT), Transference- Transference-focused therapy, and Mentalization-Based Therapy (MBT). In addition, there are ongoing improvements to the way these treatments are offered.

The treatment you need for Quiet BPD will be different depending on your circumstances. Not always, but many people with Quiet BPD have more problems with being ‘over-controlled,’ isolated, and avoidant, rather than being ‘under-controlled’ and dysregulated. That way, standard DBT or being in group therapy with others who have more ‘externalizing’, volatile ‘classic BPD’ symptoms may not be the best for you. If you have been relationally wounded and have an avoidant personality characterization, person-centered, process-driven, relational/ intersubjective therapy or a novel approach known as RO-DBT has the potential to offer something different and effective.

Diagnosing Quiet BPD can sometimes be difficult as there are no outward symptoms of distress. Because you continue to bottle up your emotions, even loved ones may not recognize the signs of your impending breakdown. But in your heart-of-hearts, you know that something is amiss, and if reading this article has laid bare your internal strife, then you may be on the verge of an epiphany. No matter what your childhood conditioning has taught you to believe, you are worthy of love, care, and healing. If you can create a safe place for your past to be processed and your pain to be channeled, your Quiet BPD will be transformed into material for your growth and connection with others.

Healing Milestones

The deepest wound of someone with Quiet BPD is that they feel undeserving. Perhaps years of childhood neglect abuse, or chronic situations led you to internalize the idea that you are someone defective who deserves less than other people.

Perhaps you were bullied and silenced, and it was never safe to express your true feelings. Maybe you were the target of toxic envy and sibling rivalry, so you learned it was safer to hide. It could also be that the adults around you were afraid of conflict and had difficulties with healthy anger, so you never learned how to act assertively.

In one way or another, you have been robbed of your childhood to serve someone else’s emotional needs. You never learned that you, too, are allowed to break down, be vulnerable, and reach out for help. Instead, whenever you get in touch with your genuine needs, all you feel is guilt and shame. Your inner critic tells you that you must be perfect to be loved, that your real self is too much for others, or that you should feel ashamed for feeling needy or vulnerable. All these beliefs further paralyze you and hinder you from going from healing to thriving. To step out of Quiet BPD is to slowly undo the deeply ingrained beliefs that have kept you in isolation and perpetuated your psychic injuries. In truth, everyone in the world, including you, is perfect in their imperfections. Slowly and gradually, allow yourself to be flawed and learn to accept that people who care for you do so in spite of your imperfections.

***

Your BPD is deemed ‘Quiet BPD’ because, from a young age, you learned that it was not safe for you to express anger. Now a part of you is convinced that it is always ‘safer’ for you to blame yourself than those you depended upon. This mechanism has followed you into adulthood; even today, you equate anger with the loss of attachment; so you would rather stifle your own wants and needs than risk ‘rocking the boat’ with anyone important in your life.

A common reaction to trauma or childhood memories related to severe emotional stress is to block them out. A part of you wants to pretend nothing bad ever happened. Even if you do remember the pain from childhood, you do not want to acknowledge that the past is still prevalent in the present and that it is hampering you from leading a full life. Perhaps you are worried that once you open the floodgate of memories and tears, they will never stop. You fear that once you start blaming your family, the anger will subsume you and destroy all your relationships.

At first, it may be unthinkable that you could tell your story without a burden of guilt or shame. But you can begin the process by engaging with an ‘enlightened witness’ such as a therapist. When you are able to do healing work in a therapeutic space, carefully crafted and held with compassion, you will realize processing trauma from the past is not only safe but essential for you to move forward in life. In a safe space, you may ‘emotional time-travel’ to when it all happened. How were you silenced and stifled? Were your innocent needs met with affection or hostility? What episodes could you recall about your childhood? The goal in therapy is not to be stuck in blame, but to release what needs to be released.

In this process, you will also learn how to befriend and manage your emotions, including unpleasant ones such as sadness, and seemingly threatening ones like anger. You can get through your emotional storms, even if they feel uncontrollable. A part of this process may be to cultivate mindfulness, so you can be an observer of your own emotions. You can learn to see that just because you are feeling something does not mean that it’s reality. You acknowledge and accept your intense feelings, but that does not mean you need to act on them.

The next step to healing is to acknowledge that the past is no longer present and that people do not have the power to hurt, threaten, or oppress you. You are much stronger than you were, and you can trust yourself. With guidance and practice, you are now capable of setting firm boundaries, acting assertively, and protecting yourself when necessary.

With humility, you may also start to see the dark consequences of passive-aggressiveness or a lack of assertiveness. These strategies may help you escape conflict on one or two occasions, but in the long run, they can be detrimental to your relationships. With some practice, however, you can undo the pattern of conflict avoidance. You can start with minimal steps, such as stating your wants and preferences on small matters. When you realize that these attempts not only do not bring about negative consequences but are welcomed, you will feel more able to take the next step.

If you have surrounded yourself with people who take advantage of your submissiveness, you may have to make some conscious effort to reshuffle and protect your interpersonal space. With deliberation, move away from people in your life who are negative, judgmental, and dominating. Instead, surround yourself with people who have the emotional capacity to support your journey of self-discovery and healing. Bear in mind that when you can authentically live as your best self, others will also benefit. Prioritizing yourself is the opposite of selfishness it is the first step to becoming the best self you can be.

Healing involves reaching out, and that may at first feel threatening to you. This process calls for tremendous courage and tenacity. You need to summon all the self-love you have for yourself, even when it feels unnatural at first. But you can achieve significant progress by putting one foot in front of the other, taking one small step at a time. One day, you will look back and be very glad you embarked on this journey towards coming out and healing.

“it is a serious thing // just to be alive / on this fresh morning / in this broken world.”

―

Reaching Out To Someone With Quiet BPD

Due to the very nature of Quiet BPD, it can be difficult to tell who might be suffering from it. Quiet BPD is also indiscriminative, affecting people from all walks of life. Those around you who appear normal or successful could be suffering in silence. They are typically highly sensitive, intuitive, and creative. When their mental health takes a downturn, however, they lose control of themselves and become vulnerable.

Most Quiet BPD sufferers live with a sense of failure and shame. They feel as though they’re lying to their friends and family or not being true to themselves. If you suspect that a friend, a loved one or a colleague is suffering from Quiet BPD, please understand that they are trying their absolute best to survive, and are in tremendous pain. However frustrated you may be, don’t try to confront them or force them to admit that they have a problem.

One of the best ways to help someone who’s struggling with Quiet BPD is to simply offer your support and make sure that they know that you’ll be there for them. You might not be able to understand exactly what’s going on inside their heart and mind, but you can make yourself available to them if they are ready to reach out.

Even though their push-pull pattern can be challenging, try not to desert or punish them. Set kind and firm boundaries, give them space to come to terms with their own struggles, and try not to patronize or attempt to rescue them.

Ultimately, understand that it is not on you to alter their path. You can be a caring but respectful ally and that is enough.

Their behavior may not make sense from your perspective, but please remember that their symptoms are a result of unspeakable pain and trauma. Whatever it is that they did or are doing, they do so to survive.

If you are able to show your friend or family member that you are there for them with an open heart, then when they feel safe enough, they will open up to you.

Many people with BPD are incredibly gifted, sensitive, and creative. They have a lot to offer the world. If they can find a way to heal from their past and learn to manage their stormy emotions, they can channel their empathy and creativity to become the best lovers, artists, and empathic leaders of the world.

I swore never to be silent whenever human beings endure suffering and humiliation.

―

Imi Lo is an independent consultant who has dedicated her career to helping emotionally intense and highly sensitive people turn their depth into strength. Her three books, Emotional Sensitivity and Intensity, The Gift of Intensity, and The Gift of Empathy, are translated into multiple languages.

Imi holds three master's degrees in Mental Health, Buddhist Studies, and Global Cultures, alongside training in philosophical counseling, Jungian psychology, and other modalities. Her multicultural perspective has been enriched by living and working across the UK, Australia, and Asia, including with organizations such as Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders and the NHS (UK). Throughout her career, she has served as a psychotherapist, art therapist, suicide crisis social worker, mental health supervisor, and trainer for mental health professionals.

You can contact Imi for a one-to-one consulting session tailored to your specific needs.